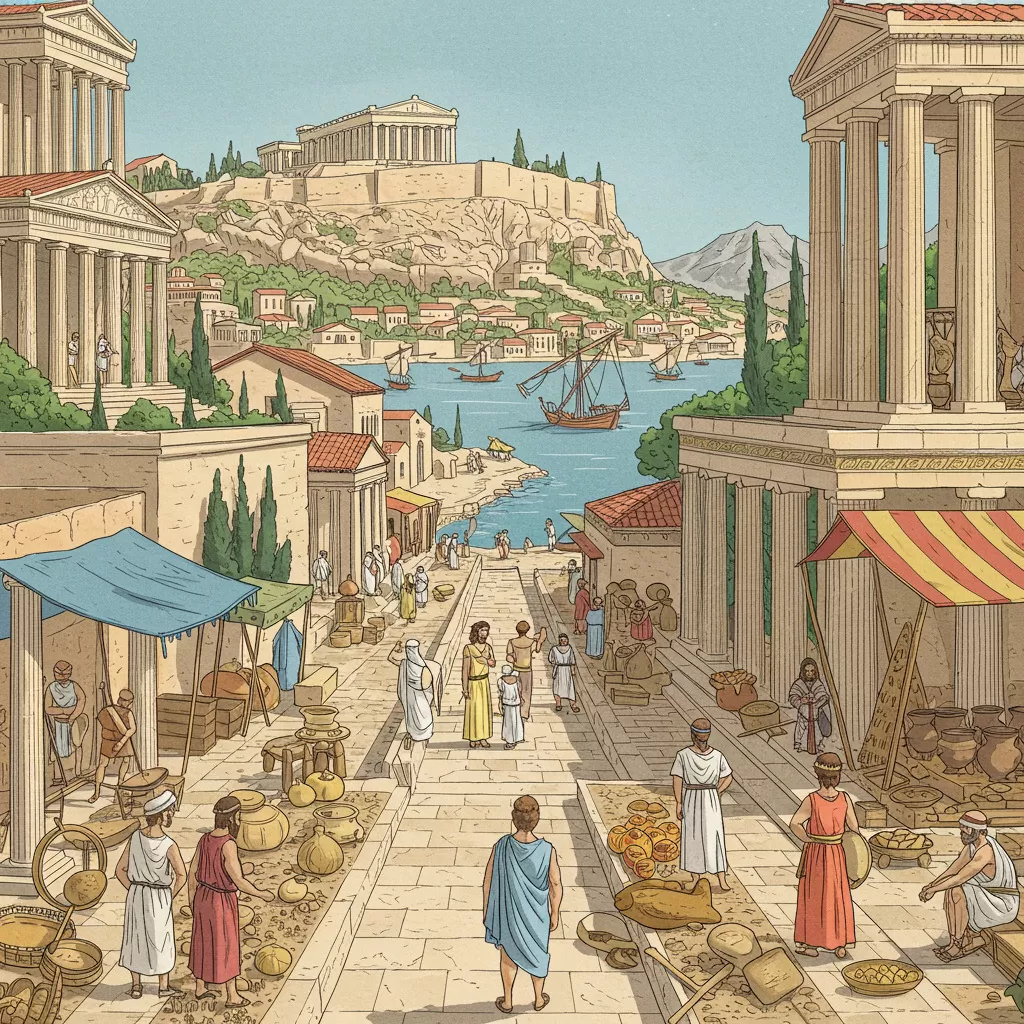

Exploring the vibrant tapestry of life in one of history's most renowned city-states reveals a fascinating glimpse into the daily existence of its inhabitants. Ancient Athens, often celebrated as the cradle of democracy and philosophy, was not only a hub of political thought but also a bustling center of social interaction, economic activity, and cultural development. Understanding the complexities of daily life in this remarkable city enables us to appreciate the foundational elements that shaped Western civilization.

From the distinct roles assigned to citizens and non-citizens to the significant impact of slavery, the social structure of Athens played a crucial role in defining the experiences of its people. Women, often relegated to the background in historical narratives, had their own unique place within this society, influencing familial and household dynamics. Meanwhile, the rhythm of daily routines, marked by morning rituals, leisure pursuits, and religious observances, painted a vivid picture of the Athenians' values and priorities.

Education and philosophy thrived in this environment, nurturing some of the greatest minds in history. The Athenian education system, coupled with the teachings of prominent philosophers, laid the groundwork for critical thinking and debate that would echo through the ages. Furthermore, the economy, driven by agricultural practices and maritime trade, underscored the city’s interconnectedness with the wider world, showcasing the entrepreneurial spirit of its citizens. Through this exploration of daily life in ancient Athens, we can unlock the stories and traditions that continue to resonate today.

The social structure of Ancient Athens was complex and unique, consisting of various classes that played distinct roles within the city-state. Understanding this structure is crucial to comprehending the daily life of Athenians, as it influenced everything from political participation to family life, and the economy.

Athens was characterized by a clear division between citizens and non-citizens. Citizens (the male population born to Athenian parents) enjoyed full rights, including the ability to vote, hold public office, and participate in the democratic process. This elite group, known as the "demos," was comprised of free men who were actively involved in political decisions and civic life. However, the criteria for citizenship were stringent; only those whose fathers were also Athenian citizens could be considered citizens. This system effectively excluded a significant portion of the population from active participation in civic life.

Non-citizens included metics, who were resident aliens, and slaves. Metics were often skilled workers or merchants who contributed to the economy but did not possess the rights of citizens. They were required to pay taxes and could serve in the military but could not vote or own land. On the other hand, slaves, who made up a considerable portion of the population, were considered property and lacked any rights. They were employed in various capacities, from household servants to skilled laborers in workshops and farms.

This division not only created a hierarchy based on citizenship but also shaped the social fabric of Athens. The citizens had the power to influence laws and policies, while non-citizens, despite their contributions, remained marginalized. The tension between these groups occasionally led to social unrest, highlighting the disparities within Athenian society.

The role of women in Ancient Athens was largely confined to the domestic sphere. Athenian women were expected to manage the household, raise children, and ensure the continuation of the family line. They were generally not allowed to participate in public life or engage in political affairs, reflecting the broader societal belief that women were inferior to men. This patriarchal structure relegated women to a position of subservience, where their primary identity was tied to their male relatives, be it their fathers or husbands.

Marriage was a significant aspect of a woman's life, typically arranged at a young age. Upon marriage, women would move into their husband's household, where they would take on the responsibilities of managing the home. While some women, particularly those from wealthier families, might have had access to education, their knowledge was generally limited to skills necessary for running a household. However, women of lower social status often worked outside the home, contributing to the family income through labor in textile production and other trades.

Despite the restrictions placed on them, some women did wield influence in other ways. For instance, priestesses held important religious roles and could attain a degree of respect in society. Notable figures like Aspasia, the partner of the statesman Pericles, showcased that women could engage in intellectual discourse and exert influence, albeit in limited contexts. Overall, the societal norms of Ancient Athens created a complex relationship between gender, power, and the public sphere.

Slavery was an integral part of Athenian society and economy. It is estimated that slaves constituted about one-third of the population in Athens. They were not merely laborers; they served in diverse roles, from domestic servants to skilled artisans and agricultural workers. The function of slaves in Athenian society was multifaceted, extending beyond manual labor to include roles such as tutors, cooks, and even clerks. This reliance on slavery allowed citizens to engage in political life and leisure activities, as the labor necessary for maintaining households and businesses was often performed by slaves.

Slavery in Athens was not based on race but rather on circumstances such as war, debt, or birth. Many slaves were prisoners of war from conquered territories or individuals who had fallen into debt. Unlike in other societies, Athenian slaves could earn their freedom; some managed to buy their freedom or were freed by their masters. However, the stigma attached to being a slave remained, and even freedmen faced discrimination and limitations in societal roles.

The moral implications of slavery were a topic of debate among contemporary philosophers and playwrights. Figures like Plato and Aristotle discussed the ethics of slavery, often rationalizing it as a natural hierarchy. Nonetheless, the economic reliance on slavery was a cornerstone of Athenian wealth and prosperity, fueling its art, culture, and military endeavors.

In summary, the social structure of Ancient Athens was characterized by clear distinctions between citizens and non-citizens, with women and slaves occupying marginalized roles. This complex hierarchy shaped the daily lives of Athenians, influencing their interactions, responsibilities, and opportunities within the city-state. Understanding these dynamics is essential for comprehending the broader aspects of Athenian culture and society.

Daily life in ancient Athens was a complex tapestry woven from various activities and routines that shaped the lives of its citizens. The rhythm of life was dictated by the sun, societal roles, and cultural practices. From the break of dawn until dusk, Athenians engaged in a multitude of tasks that ranged from work and education to leisure and religious observance. Understanding these daily activities provides crucial insight into the values, social norms, and priorities of Athenian society.

The day in ancient Athens typically began at dawn. Citizens would awaken to the sound of roosters crowing, signaling the start of a new day. Morning rituals often included personal grooming and offerings to the household gods, a practice that underscored the importance of religion in daily life. Many Athenians would offer prayers or sacrifices to deities such as Hestia, the goddess of the hearth, to ensure blessings for their homes and families.

After their morning rituals, men would typically head out for work. The Athenian economy was diverse, with many citizens engaged in various trades and professions. Artisans, farmers, merchants, and laborers formed the backbone of the economy. The Agora, the central public space in Athens, was a hub of activity where men gathered to conduct business, exchange ideas, and participate in political discourse. The Agora was not just a marketplace; it was a vibrant center of social interaction and civic life.

For farmers, the early hours were dedicated to tending to their fields. Agriculture was crucial for Athenian society, and the cultivation of crops such as olives, grapes, and grain was labor-intensive. Farmers would often work alongside their families, emphasizing the communal aspect of agricultural life. The importance of agriculture was reflected in Athenian literature, with many references to the blessings of a good harvest and the hardships of poor yields.

Women, on the other hand, had a different routine. While some women from wealthier families might have overseen household management and engaged in textile production, the majority of women were confined to domestic duties. Their day would involve tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and caring for children. Although their work was vital for the family unit and the economy, it often went unrecognized in the public sphere.

Leisure was an essential aspect of life in ancient Athens, particularly for male citizens. After a long day of work, many would gather in public spaces to socialize and enjoy various forms of entertainment. The Athenian calendar was filled with festivals and theatrical performances that provided opportunities for relaxation and enjoyment.

Sporting events were a significant part of Athenian life, with the Panathenaic Festival being one of the most notable celebrations. This festival honored the goddess Athena and included athletic competitions, such as running, wrestling, and chariot racing. Victors were celebrated and often received prizes, which could elevate their social status within the community.

Theater was another beloved form of entertainment. Athens was the birthplace of dramatic arts, and playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides produced works that are still celebrated today. Citizens would flock to the theaters to witness tragedies and comedies, engaging with the themes of morality, politics, and human emotion explored in the performances. The theater was a communal experience that fostered discussion and reflection among the audience.

For women and non-citizens, leisure activities were more constrained. While they might participate in domestic festivities or religious rituals, their opportunities for public entertainment were limited. However, some women did engage in social gatherings, particularly during festivals, where they could enjoy music, dance, and other forms of cultural expression.

Religion permeated every aspect of daily life in ancient Athens, and various rituals and festivals punctuated the calendar year. The Athenian pantheon was rich with gods and goddesses, each associated with different aspects of life and nature. Major religious festivals were not only a time for worship but also served as communal gatherings that reinforced social bonds.

The most significant festival was the Panathenaea, held in honor of Athena, the city's patron goddess. This festival included a grand procession, athletic competitions, and elaborate sacrifices at the Acropolis. Citizens would participate in the procession, showcasing their pride in their city and their devotion to the goddess. The Panathenaea was a time of unity and celebration, drawing Athenians together in a shared cultural experience.

Other important festivals included the Dionysia, dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility. This festival featured dramatic performances and competitions that highlighted the artistic achievements of Athens. The religious significance of these festivals was intertwined with their social functions, allowing citizens to reflect on their identities, values, and communal ties.

Religious practices in daily life extended beyond festivals. Athenians conducted daily offerings and rituals to secure favor from the gods. Households maintained altars to worship deities and ancestors, and the act of sacrifice was an essential part of maintaining religious piety. Such practices underscored the belief that divine favor was essential for personal and communal well-being.

In conclusion, daily life in ancient Athens was characterized by a rich blend of work, leisure, and religious observance. The routines of Athenians were deeply influenced by their social structure, religious beliefs, and cultural values. Understanding these daily activities not only sheds light on the practical aspects of life in ancient Athens but also reveals the underlying philosophies and ideals that shaped one of history's most influential civilizations.

Education and philosophy in ancient Athens were cornerstones of Athenian life, deeply intertwined with the cultural and political fabric of the city-state. The Athenian education system was designed not only to impart knowledge but also to cultivate virtuous citizens capable of participating in the democratic processes of their society. This section explores the Athenian education system, the prominent philosophers who shaped Athenian thought, and the essential role of rhetoric and debate in both education and public life.

The education system in ancient Athens varied significantly depending on one's social class and gender. Education was primarily reserved for male citizens, who began their formal schooling around the age of seven. The curriculum was comprehensive, encompassing reading, writing, arithmetic, music, and physical education. Boys attended schools known as grammateia, where they learned under the guidance of a grammatistes (teacher).

Physical education was considered vital for developing a strong body and was primarily conducted at institutions known as palaestrae. Athletic training was not merely for competition; it was integral to the Athenian ideal of a well-rounded citizen. In addition to physical training, boys also received instruction in music, which was an essential aspect of Athenian culture. Music education not only included learning to play instruments but also involved singing and understanding the theory of music.

After completing elementary education, boys typically entered a phase of advanced training, focusing on rhetoric, philosophy, and public speaking. This was often conducted by renowned philosophers and sophists who had established schools of thought in Athens. The education system aimed to prepare young men for their roles as active participants in the democratic processes of Athens.

In stark contrast, education for girls was limited and primarily focused on domestic skills. Girls were generally educated at home, learning household management, weaving, and other skills necessary for managing a home. Although some women from affluent families had access to education, it was rarely formalized, emphasizing the societal belief that women’s primary role was within the home.

Athens was the cradle of Western philosophy, giving rise to many influential thinkers whose ideas have persisted through the ages. Among the most notable philosophers were Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, each contributing unique perspectives that shaped Athenian education and society.

Socrates, often regarded as the father of Western philosophy, introduced the Socratic method, a form of inquiry and dialogue intended to stimulate critical thinking and illuminate ideas. His approach emphasized questioning and dialogue as tools for gaining knowledge and understanding ethical concepts. Socrates did not leave behind any written works; instead, his teachings were recorded by his students, notably Plato. His focus on ethics and virtue had a profound impact on Athenian education, encouraging students to think critically about morality and their civic responsibilities.

Plato, a student of Socrates, founded the Academy, one of the earliest institutions of higher learning in the Western world. His works, particularly “The Republic,” explored the nature of justice, the ideal state, and the role of the philosopher-king. Plato’s emphasis on philosophical education as a means to achieve a just society became a central tenet in Athenian thought. He believed that education should not only impart knowledge but also cultivate the soul and character of individuals, preparing them for leadership roles in society.

Aristotle, a student of Plato, further expanded on his teacher's ideas, emphasizing empirical observation and the importance of logic. His works covered a vast array of subjects, including ethics, politics, metaphysics, and biology. Aristotle's concept of the "Golden Mean," advocating for moderation and balance in all aspects of life, became fundamental in both personal ethics and political philosophy. His influence on education was profound, as he believed that education should be comprehensive, integrating physical, moral, and intellectual development.

Rhetoric, the art of persuasive speaking and writing, played a pivotal role in Athenian education and public life. It was considered an essential skill for any citizen wishing to participate in the democratic processes of Athens. The ability to articulate ideas clearly and persuasively was crucial for engaging in debates, participating in the assembly, and representing oneself in legal matters.

The Sophists, a group of itinerant teachers and philosophers, were instrumental in popularizing rhetoric. They offered education in persuasive speaking, emphasizing the techniques of argumentation and the ability to construct compelling narratives. Sophists believed that knowledge could be subjective and that effective rhetoric could sway public opinion and influence decision-making.

Formal training in rhetoric often involved studying the works of earlier orators and practicing speeches. Students learned to analyze arguments, develop counterarguments, and present their ideas convincingly. The practice of public speaking wasn’t limited to formal education; it extended into public forums, where citizens often debated issues of the day, demonstrating the practical application of their rhetorical training.

Athenian democracy relied heavily on these skills, as decisions were made through public debate and consensus. Citizens gathered in the Agora, the heart of civic life, to discuss policies, propose laws, and deliberate on matters of state. The ability to persuade one’s fellow citizens was not merely an academic exercise but a vital component of civic engagement and responsibility.

In conclusion, education and philosophy in ancient Athens were fundamental to the development of a democratic society. The Athenian education system, although exclusive, played a crucial role in preparing citizens for active participation in public life. Philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle profoundly influenced the intellectual landscape of Athens, emphasizing the importance of ethics, knowledge, and civic duty. Rhetoric and debate were not only tools of education but also the lifeblood of Athenian democracy, enabling citizens to engage in meaningful discourse and shape the future of their city-state.

The economy of ancient Athens was complex and multifaceted, characterized by a blend of agriculture, trade, and craftsmanship that supported one of the most powerful city-states of the classical world. As the heart of democracy, philosophy, and art, Athens thrived economically, allowing its citizens to engage in various activities that fueled both their livelihood and cultural advancements. This section examines the critical components of the Athenian economy, focusing on agricultural practices, maritime trade, and the currency system that facilitated economic exchange.

Agriculture was the backbone of the Athenian economy, providing sustenance for its population and surplus for trade. The fertile plains surrounding Athens, particularly in regions like Attica, were crucial for cultivating various crops. The primary agricultural products included grains, olives, and grapes, which played a significant role in the diet and economy of the Athenians.

Land ownership was a marker of wealth and status in Athens. Wealthy citizens, known as aristocrats, owned large estates and often employed laborers or slaves to work the land. In contrast, poorer citizens engaged in small-scale farming, often struggling to maintain their livelihoods. The agrarian calendar dictated the daily routines of farmers, with planting and harvesting seasons requiring intense labor and cooperation among families and neighbors.

Crop rotation and the use of simple tools were common practices among Athenian farmers. They cultivated their fields with wooden plows drawn by oxen and relied on hand tools for planting and harvesting. Despite challenges such as drought or poor soil, the Athenians were skilled in managing their agricultural practices, which played a crucial role in sustaining the city-state and its economy.

Due to its advantageous geographical location, Athens became a dominant maritime power, relying heavily on trade to supplement its agricultural output. The city-state's access to the Aegean Sea provided an avenue for commerce, facilitating the exchange of goods with other regions. Athenian ships, known for their speed and agility, navigated the waters to establish trade routes that extended as far as Egypt, Persia, and Sicily.

Trade was not limited to agricultural products; Athenians imported a variety of goods, including:

The Agora, the central public space in Athens, served as the bustling marketplace where merchants and citizens gathered to buy and sell goods. This economic hub was not only a center for commerce but also a social and political focal point, where citizens engaged in discussions and debates about various topics, including trade policies and economic strategies.

Trade also played a critical role in the emergence of Athenian democracy. As merchants and traders accumulated wealth from commerce, they gained influence and power, which contributed to the gradual shift in political structures, allowing for broader participation in governance.

To facilitate trade and economic transactions, Athens developed a sophisticated monetary system. The introduction of coinage in the 6th century BCE marked a significant advancement in the economy. The Athenian silver tetradrachm became a widely accepted currency, recognized for its purity and weight, making it a preferred medium of exchange throughout the Mediterranean.

| Coin Type | Weight (grams) | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Tetradrachm | 17.2 | Equivalent to four drachmas |

| Drachma | 4.3 | Basic unit of currency |

| Obol | 0.9 | 1/6 of a drachma |

The use of coins revolutionized trade, allowing for easier transactions and the ability to assign value to goods and services. Coins were often minted with symbols and images that reflected Athenian culture, such as the owl, a symbol of Athena, the city's patron goddess, which further connected the economy with its cultural identity.

Moreover, the Athenian economy was intricately linked to its military endeavors. The wealth amassed through trade and agriculture funded the powerful Athenian navy, which was essential for protecting trade routes and enhancing Athenian influence across the Aegean Sea. This interdependence between economy and military power underscored the strategic importance of trade in maintaining Athenian dominance.

In summary, the economy and trade in ancient Athens were integral to the city's prosperity and cultural achievements. Through effective agricultural practices, robust maritime trade, and the use of a sophisticated currency system, Athens not only sustained its population but also fostered a vibrant society that contributed to the advancements in philosophy, art, and governance that would leave a lasting legacy on Western civilization.