The Hellenistic period, a remarkable era in ancient history, witnessed the flourishing of diverse philosophical thought that profoundly shaped the intellectual landscape of the time. Emerging from the ashes of classical Greece, this vibrant period was marked by a shift in focus from the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake to the application of philosophy as a means of achieving a fulfilling life. As the conquests of Alexander the Great spread Greek culture across vast territories, the interplay of various traditions and ideas led to the development of new schools of thought, each offering unique perspectives on the nature of existence, ethics, and the pursuit of happiness.

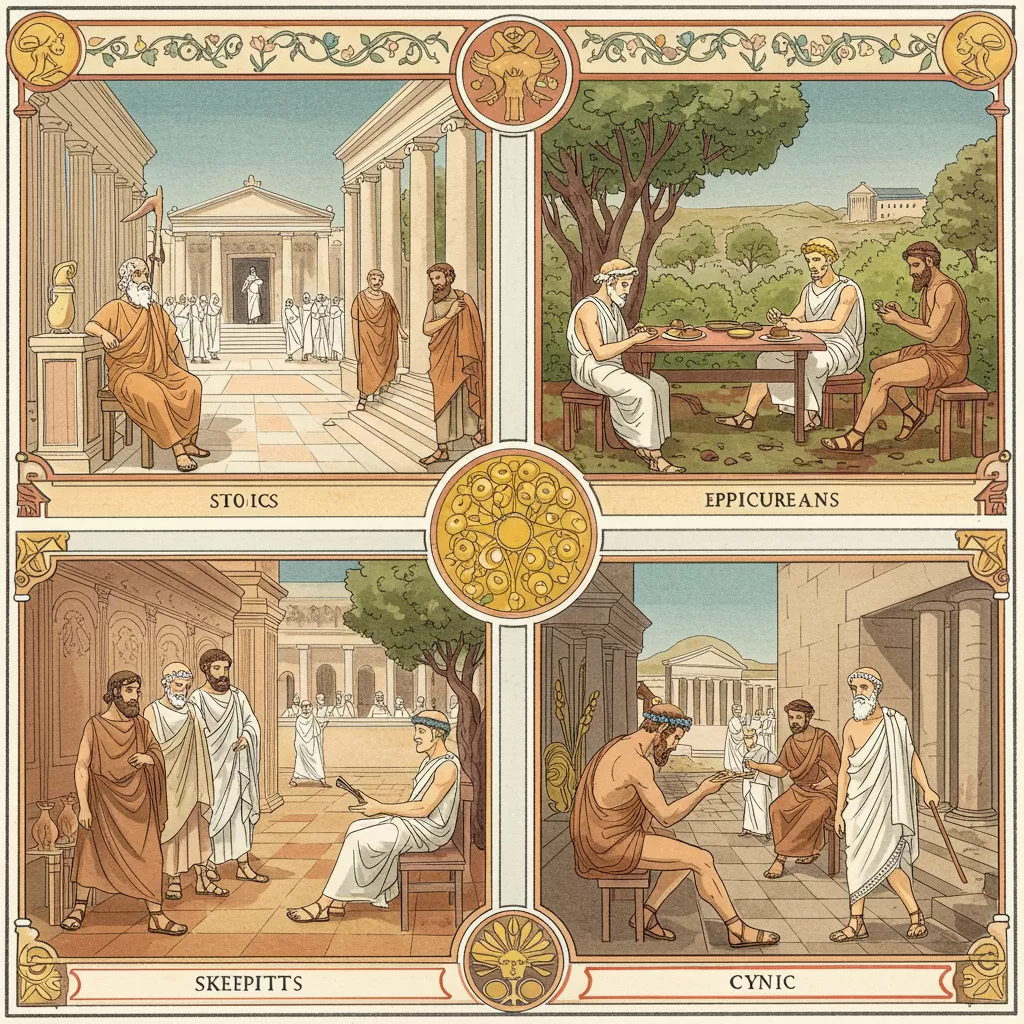

At the heart of Hellenistic philosophy lies a quest for answers to fundamental questions about human existence. Thinkers grappled with issues of ethics, the nature of the universe, and the means to attain tranquility amidst a rapidly changing world. The period is characterized by a rich tapestry of philosophical schools, each with its own doctrines and methodologies. Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism emerged as prominent movements, each proposing distinct pathways to understanding and navigating the complexities of life.

As we delve into the intricacies of these philosophical schools, we will explore the lives and teachings of their foremost thinkers. From the resilient Stoics who emphasized virtue and reason to the Epicureans who celebrated pleasure as a key to happiness, and the Skeptics who questioned the very foundations of knowledge, each school offers timeless insights that continue to resonate in contemporary discussions. Understanding the legacy of Hellenistic philosophy not only enriches our appreciation of ancient thought but also illuminates its enduring influence on modern philosophy and beyond.

The Hellenistic period, spanning from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the emergence of the Roman Empire in 31 BCE, was a time of significant transformation in the cultural, political, and intellectual landscape of the Mediterranean. This era witnessed the spread of Greek culture and thought across a vast empire, leading to the birth of various philosophical schools that sought to address the fundamental questions of life, existence, and ethics. Hellenistic philosophy, therefore, represents a rich tapestry of ideas that emerged in response to the challenges posed by a changing world.

The historical backdrop of the Hellenistic period is marked by the conquests of Alexander the Great, which facilitated the dissemination of Greek culture throughout the regions he conquered, including Egypt, Persia, and parts of India. After Alexander's death, his empire fragmented into several kingdoms ruled by his generals, known as the Diadochi. This political fragmentation led to the establishment of new centers of power and culture, such as Alexandria in Egypt, which became a hub for intellectual activity.

During this time, the traditional city-state structure of Greece began to decline, and with it, the old philosophical schools that were closely tied to civic life. The focus of philosophy shifted from the public sphere to individual concerns, such as ethics, the nature of happiness, and the quest for knowledge. The uncertainties of the political landscape, coupled with the rise of individualism, prompted philosophers to seek answers to existential questions and to formulate systems that could provide guidance in an uncertain world.

Hellenistic philosophers grappled with several key questions, many of which remain relevant today. Central themes included:

Philosophers sought to provide frameworks for living a good life amid the turmoil of the Hellenistic world. Their ideas often reflected a departure from earlier philosophical traditions, such as those established by Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, focusing instead on practical ethics and personal well-being.

The Hellenistic period, spanning from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the rise of the Roman Empire, was a time of immense cultural and philosophical development. During this era, three major philosophical schools emerged: Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism. Each of these schools offered unique perspectives on ethics, knowledge, and the nature of reality, reflecting the diverse intellectual landscape of the time.

Founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium in the early 3rd century BCE, Stoicism became one of the most influential schools of thought in the Hellenistic period. The central tenet of Stoicism is the idea that virtue, understood as living in accordance with nature and reason, is the only true good. Stoics believed that external circumstances, including wealth, health, and social status, are indifferent and should not dictate one's happiness.

Stoicism teaches that individuals should strive for apatheia, a state of inner peace and freedom from emotional disturbance. This is achieved through the practice of self-control, rationality, and the cultivation of wisdom. The Stoics emphasized the importance of understanding the natural order of the universe, which they believed operated according to rational principles.

Key thinkers of the Stoic school included:

Stoicism had a profound impact on Roman philosophy and later Christian thought. Its emphasis on virtue and reason as the path to a good life resonated with many subsequent philosophical and religious traditions.

Epicureanism, founded by Epicurus in the late 4th century BCE, presents a contrasting view to Stoicism. This school holds that the pursuit of happiness is the ultimate goal of life, and that pleasure, understood as the absence of pain and disturbance, is the highest good. Epicurus distinguished between different types of pleasures, advocating for intellectual and moderate pleasures over purely physical ones.

Epicureanism teaches that understanding the nature of the universe can lead to tranquility and happiness. Epicurus posited that the universe was made up of atoms and void, a materialistic view that emphasized natural explanations for phenomena rather than supernatural ones. This atomistic worldview allowed individuals to find peace by understanding that death is simply the cessation of sensation and should not be feared.

Key tenets of Epicureanism include:

Epicureanism was influential in the Hellenistic world and later in the Roman Empire. However, it faced criticism from Stoics and other philosophical schools, which viewed its emphasis on pleasure as overly hedonistic. Despite this, the underlying message of seeking happiness through rational thought and moderation has continued to resonate through the ages.

Skepticism arose as a reaction to the dogmatic assertions of both Stoicism and Epicureanism. The Skeptics, particularly the Academic Skeptics and the Pyrrhonists, questioned the possibility of certain knowledge. They argued that human perception and reasoning are inherently flawed and that individuals should suspend judgment on beliefs and claims that cannot be definitively proven.

Academic Skepticism, associated with philosophers such as Arcesilaus and Carneades, emerged from Plato's Academy. It posited that while knowledge is unattainable, one can still engage in debate and discussion to arrive at probable opinions. This form of skepticism did not advocate for complete doubt but rather encouraged a critical approach to knowledge.

Pyrrhonism, founded by Pyrrho of Elis, took a more radical approach. Pyrrho advocated for complete suspension of belief (epoché) and aimed for a state of mental tranquility by relinquishing the need for certainty. The Pyrrhonists believed that by acknowledging the limits of human understanding, one could achieve a serene state of mind.

Key aspects of Skepticism include:

Skepticism played a crucial role in shaping the discourse of the Hellenistic period and laid the groundwork for later philosophical developments, including those in the Roman and early modern eras. Its influence can be seen in the works of philosophers such as Descartes and Hume, who grappled with questions of knowledge and certainty.

In summary, the philosophical schools of the Hellenistic era—Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism—offered diverse and profound insights into human existence, ethics, and knowledge. Each school represented distinct approaches to understanding the world and navigating the complexities of life, and their legacies continue to resonate in contemporary philosophical discussions.

The Hellenistic period, which followed the conquests of Alexander the Great, was a time of significant philosophical development. During this era, several schools of thought emerged, each contributing uniquely to the understanding of ethics, knowledge, and the nature of reality. This section explores three pivotal figures from this period: Zeno of Citium, Epicurus, and Pyrrho, elucidating their philosophies and lasting impacts.

Zeno of Citium (c. 334–262 BCE) is widely regarded as the founder of Stoicism, a school of thought that profoundly influenced both ancient and modern philosophy. Born in Citium, a city in Cyprus, Zeno's philosophical journey began after a shipwreck led him to Athens, where he immersed himself in the teachings of Socrates, the Cynics, and other philosophers of the time.

Stoicism is characterized by its focus on virtue and wisdom as the highest goods, advocating that the path to happiness is found through living in accordance with nature and reason. Zeno posited that emotions result from errors in judgment, and thus, by cultivating rational thought and controlling one's desires, individuals could achieve a state of tranquility and freedom from suffering.

Central to Zeno’s teachings was the idea of logos, often translated as "reason" or "rational principle." He believed that the universe is governed by a divine rationality, and understanding this cosmic order is essential for leading a virtuous life. Zeno's emphasis on personal ethics, self-control, and resilience in the face of adversity laid the groundwork for Stoic philosophy, which would later be expanded upon by his successors, including Cleanthes and Chrysippus.

Moreover, Zeno's contributions to logic, particularly in the realm of propositional logic, were significant. He introduced the concept of a syllogism, which would influence later philosophical thought. His works, although largely lost, are acknowledged through the writings of later philosophers, illustrating the enduring nature of his ideas.

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) founded the school of philosophy known as Epicureanism, which emphasized the pursuit of happiness through the cultivation of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Born on the island of Samos, he eventually settled in Athens, where he established his school, known as the "Garden." This location was not only a physical space but also a symbol of a community centered around philosophical discourse and mutual support.

Epicurus proposed that the greatest good is to seek pleasure and avoid pain, but he distinguished between different types of pleasures. He advocated for hedonism in a nuanced way, arguing that the most fulfilling pleasures are those of the mind rather than the body. Simple pleasures, such as friendship, intellectual pursuits, and the appreciation of nature, were deemed more valuable than indulgent or fleeting physical pleasures.

One of Epicurus's significant contributions to philosophy was his formulation of the Fourfold Remedy, which outlines the key elements to achieving happiness:

This remedy reflects Epicurus's belief that many of the fears and anxieties that plague individuals stem from misconceptions about the nature of existence and the universe. By dispelling these fears, individuals can focus on cultivating a life filled with joy and contentment.

Epicurus also advanced the understanding of atomic theory, positing that everything in the universe is composed of small, indivisible particles (atoms) moving through the void. This scientific approach to philosophy allowed him to address existential questions while maintaining a focus on empirical evidence and rational thought.

Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360–270 BCE) is recognized as the father of Skepticism, a philosophical school that questioned the possibility of certain knowledge. His life was marked by travel, including a significant journey to India, where he encountered different philosophical ideas, potentially influencing his skeptical approach.

Pyrrho's philosophy revolved around the notion that humans cannot access ultimate truths about the world. He argued that since senses can deceive and reason can lead to contradictory conclusions, the best course of action is to suspend judgment about beliefs and assertions. His central tenet was epoche, meaning a state of mental tranquility achieved by withholding belief.

Pyrrho's teachings emphasized the importance of ataraxia, or peace of mind, which can be achieved through the acceptance that certainty is unattainable. This perspective encouraged followers to focus on practical living and to adopt a stance of acceptance towards the uncertainties of life.

While Pyrrho wrote little himself, his ideas were recorded and expanded upon by later skeptics such as Aenesidemus and Sextus Empiricus. His influence extended beyond his time, contributing to the development of both academic skepticism and Pyrrhonian skepticism, which questioned the validity of knowledge claims and the criteria by which we determine truth.

In summary, Zeno, Epicurus, and Pyrrho represent the diversity of thought during the Hellenistic period. Their philosophies not only addressed the pressing concerns of their time but also laid foundational ideas that would influence philosophical discourse for centuries to come. The interplay between ethical living, the pursuit of happiness, and the skepticism of knowledge continues to resonate in contemporary philosophical discussions, illustrating the lasting legacy of these influential thinkers.

The Hellenistic period, emerging after the death of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BCE and extending until the rise of the Roman Empire, was a time of profound change and development in philosophical thought. This era produced a rich tapestry of ideas that not only shaped the intellectual landscape of the time but also cast long shadows over subsequent philosophical traditions. The impact of Hellenistic philosophy can be observed in several key areas: its influence on Roman philosophy, its legacy in the realm of modern philosophical thought, and its relevance in contemporary discussions.

The philosophical developments of the Hellenistic period laid the groundwork for the flourishing of thought in the Roman Empire. Roman philosophers, particularly during the early Empire, drew extensively from Hellenistic schools, notably Stoicism and Epicureanism. The adoption of these schools was not merely a matter of intellectual inheritance but also a practical response to the sociopolitical environment of Rome, which was marked by rapid expansion and cultural diversity.

Stoicism, with its emphasis on virtue, self-control, and rationality, resonated deeply with Roman values. Prominent figures such as Seneca, Epictetus, and the Emperor Marcus Aurelius integrated Stoic principles into their writings and lives. Seneca’s letters and essays reflect a commitment to Stoic ethics, emphasizing the importance of moral integrity and the cultivation of inner peace amidst external chaos. In his "Meditations," Marcus Aurelius articulates Stoic ideas, providing a personal reflection on how to live virtuously in a world filled with challenges and uncertainties.

Epicureanism, while perhaps less influential than Stoicism among the elite of Rome, still found a significant following. The Roman poet Lucretius, in his work "De Rerum Natura," presents Epicurean philosophy as a means of achieving happiness through the pursuit of knowledge and understanding the natural world. His poetic exposition of Epicurean ideas contributed to the dissemination of Hellenistic thought, making it more accessible to the general populace.

The synthesis of Hellenistic ideas with Roman thought resulted in a unique philosophical tradition that emphasized ethics and practical wisdom. This blend was crucial not only for the development of Roman intellectual life but also for the preservation and transmission of Hellenistic ideas, which would later influence the Christian philosophers of the late antiquity.

The legacy of Hellenistic philosophy extends well into modern philosophical thought, particularly in the areas of ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics. The principles espoused by Stoics and Epicureans have found resonance in various philosophical movements throughout history, including Enlightenment thought and contemporary philosophy.

In the realm of ethics, Hellenistic ideas about virtue, happiness, and the nature of the good life continue to inform modern discussions. The Stoic emphasis on rationality and emotional resilience has been revitalized in recent years through the lens of positive psychology. Modern thinkers advocate for Stoic practices such as mindfulness and cognitive reframing as tools for enhancing well-being and coping with the stresses of contemporary life.

Epicureanism's focus on the pursuit of pleasure, understood as the absence of pain and the cultivation of simple joys, has influenced modern hedonistic philosophies. However, contemporary interpretations often emphasize a more nuanced understanding of pleasure, aligning it with personal fulfillment and ethical living rather than mere indulgence.

Additionally, Hellenistic skepticism has paved the way for modern epistemological inquiries. The questions raised by the Skeptics about the nature of knowledge and belief resonate with contemporary debates in philosophy, especially concerning relativism and the limits of human understanding. The methodological skepticism of thinkers like René Descartes can be traced back to the questions posed by Pyrrhonian skeptics, who challenged the certainty of knowledge.

Today, Hellenistic philosophy remains a vibrant part of philosophical discourse. The practical applications of Stoicism, in particular, have gained significant traction in modern society. Self-help literature, coaching, and therapeutic practices often draw on Stoic principles to help individuals navigate the complexities of life. For example, the concept of distinguishing between what is within our control and what is not has become a cornerstone of cognitive-behavioral therapy, reflecting Stoic thought's enduring relevance.

Moreover, discussions surrounding ethics in the context of technology and bioethics often invoke Hellenistic ideas. The Stoic commitment to universal reason and moral duty provides a framework for addressing contemporary ethical dilemmas, such as those posed by artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and environmental concerns. Philosophers and ethicists engage with Hellenistic thought to explore how ancient insights can inform modern challenges.

In the academic realm, scholars continue to investigate the nuances of Hellenistic philosophy, seeking to understand its implications for modern philosophical questions. Interdisciplinary approaches that connect Hellenistic ideas with psychology, political theory, and cultural studies are increasingly common. This reflects a broader trend in philosophy that emphasizes the interconnectedness of different fields of knowledge.

Furthermore, the resurgence of interest in mindfulness and well-being practices has led to a revival of Stoic and Epicurean thought, as individuals seek ancient wisdom to address contemporary existential questions. This trend highlights the enduring power of Hellenistic philosophy to provide insights into the human condition, offering tools for navigating life's uncertainties.

In summary, the impact of Hellenistic philosophy on later thought is profound and multifaceted. From its significant influence on Roman philosophy to its lasting legacy in modern ethical discussions and contemporary practices, Hellenistic ideas continue to shape our understanding of the world and ourselves. The philosophical inquiries initiated during this period remain relevant, inviting us to engage with the profound questions of existence, ethics, and knowledge that transcend time and culture.