In the vast landscape of philosophical thought, few concepts resonate as profoundly as the idea of a fulfilling and meaningful life. This notion, deeply embedded in the works of ancient thinkers, invites us to explore the intricate relationship between virtue, happiness, and the essence of human existence. At the heart of this exploration lies a pivotal concept that has shaped ethical discussions for centuries, urging individuals to seek a life well-lived through the cultivation of their character and virtues.

As we delve into the nuances of this philosophical framework, we uncover a rich historical context that informs its development. By examining the interplay of moral and intellectual virtues, we gain insights into the foundational principles that guide ethical behavior and decision-making. This journey not only sheds light on the pursuit of personal fulfillment but also emphasizes the significance of community and interpersonal relationships in achieving a life of purpose and joy.

Moreover, engaging with contemporary critiques and interpretations allows us to appreciate the enduring relevance of this ancient philosophy. By comparing it with other ethical theories, we can better understand the diverse perspectives on what it means to lead a good life, enriching our understanding of happiness and its distinctions from mere pleasure. Join us as we navigate this profound philosophical terrain, uncovering the timeless wisdom that continues to inspire and challenge us today.

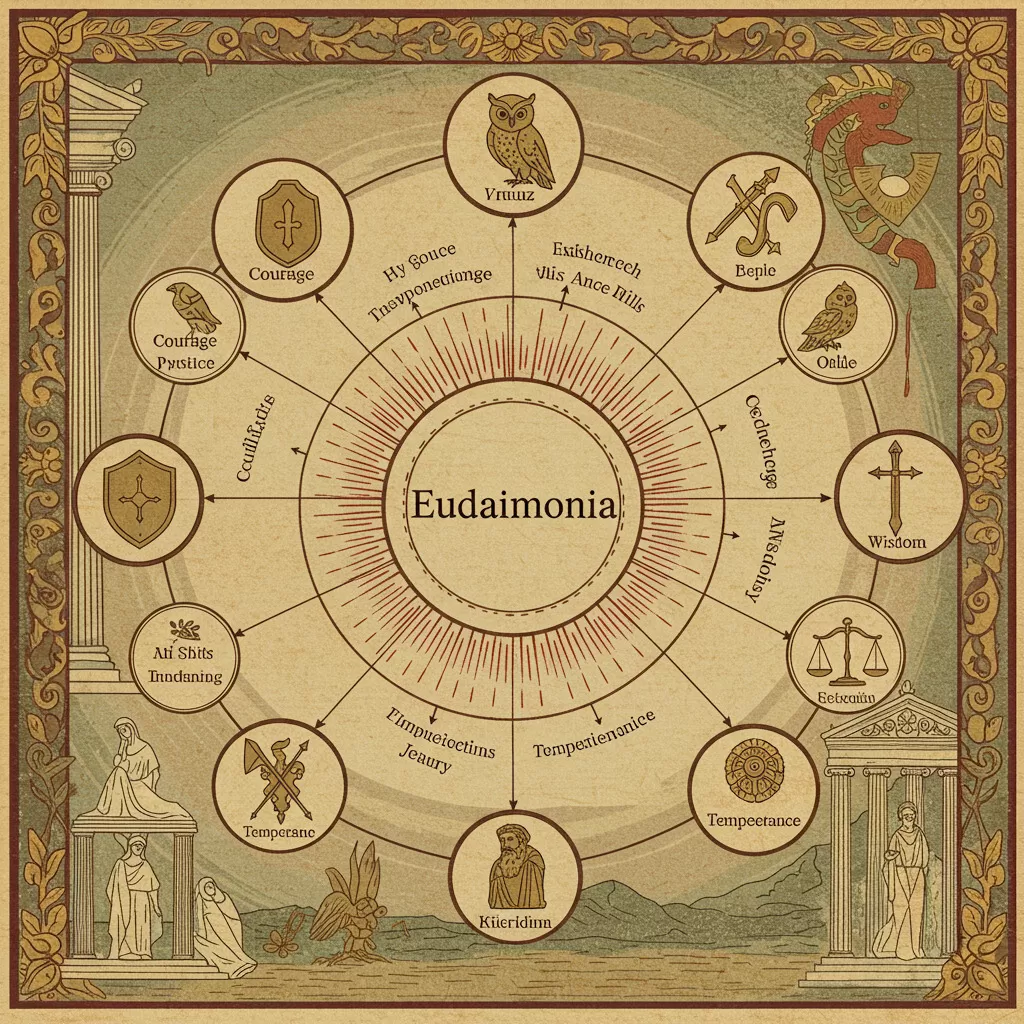

The concept of eudaimonia, often translated as "happiness" or "flourishing," occupies a central place in the ethical framework established by Aristotle in his seminal work, the Nicomachean Ethics. To comprehend eudaimonia fully, one must delve into both its definition and the historical context surrounding Aristotelian ethics. This exploration reveals not only the nuances of Aristotle's thoughts but also the implications of eudaimonia in the pursuit of a meaningful and virtuous life.

Aristotle defines eudaimonia as the highest good for human beings, an end in itself that is desirable for its own sake. Unlike transient states of pleasure or happiness derived from external circumstances, eudaimonia reflects a more profound, enduring state of being that arises from living in accordance with virtue. Aristotle posits that eudaimonia is achieved through the practice of virtue and the cultivation of one’s character over a lifetime.

Aristotle famously states, “Eudaimonia is the activity of the soul in accordance with virtue.” This definition emphasizes that eudaimonia is not merely a feeling but an active engagement with life that aligns with moral and intellectual virtues. He argues that every action and decision aims toward some good, and the highest of these goods is eudaimonia. In this sense, eudaimonia is closely linked to the concept of telos, or purpose. Each individual has a unique purpose that they must strive to fulfill to achieve true happiness.

Furthermore, Aristotle distinguishes between two types of goods: those that are instrumental (means to an end) and those that are intrinsic (ends in themselves). Eudaimonia is categorized as an intrinsic good, which means it is worthwhile in itself and not merely a stepping stone to something else. This perspective underscores the importance of living a life that transcends mere pleasure-seeking and aligns with a deeper sense of fulfillment.

To fully appreciate the concept of eudaimonia, it is essential to understand the historical backdrop of Aristotle's philosophy. Living in the 4th century BCE, during a time of significant political and social change in Athens, Aristotle's thoughts were influenced by his predecessors, particularly Socrates and Plato. Socrates emphasized ethical inquiry and the importance of virtue, while Plato introduced the notion of ideal forms and the quest for knowledge as pathways to understanding the good life.

Aristotle, however, diverged from his teacher Plato by grounding his ethical theories in the reality of human experiences and the natural world. He believed that knowledge and virtue arise from practical engagement with life rather than abstract theorizing. In this historical context, eudaimonia emerges as a response to the philosophical debates of the time, seeking to establish a more pragmatic approach to ethics that emphasizes the importance of virtues cultivated within a community.

Moreover, Aristotle’s work took place against the backdrop of the polis, or city-state, which served as the center of social and political life in ancient Greece. The communal nature of Greek society influenced his understanding of eudaimonia as not just an individual pursuit but a collective endeavor that requires social engagement and the fulfillment of one’s role within the community.

Through his exploration of eudaimonia, Aristotle asserts that ethical living is intrinsically linked to human nature and society. This perspective laid the groundwork for subsequent ethical theories and continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about the good life and moral philosophy.

In Aristotelian ethics, the concept of virtue is central to the attainment of eudaimonia, often translated as "happiness" or "flourishing." Aristotle posits that eudaimonia is the ultimate goal of human life, and it is achieved through the practice of virtue. This section delves into the different types of virtues, the Doctrine of the Mean, and how these elements intertwine to facilitate the pursuit of a fulfilled and meaningful life.

Aristotle categorizes virtues into two main types: moral virtues and intellectual virtues. Each type plays a distinct role in the development of character and the achievement of eudaimonia.

Moral Virtues are qualities that govern our emotions and actions, shaping our character through habits. Aristotle argues that moral virtues are developed through practice and social interaction. Examples of moral virtues include courage, temperance, and justice. For instance, courage enables individuals to confront fear and act rightly in the face of danger, while temperance helps in moderating desires and pleasures. According to Aristotle, moral virtues are crucial because they help us navigate the complexities of life and make ethical decisions that contribute to our overall well-being.

Intellectual Virtues, on the other hand, are related to the mind and the pursuit of knowledge, wisdom, and understanding. These virtues include theoretical wisdom (sophia), practical wisdom (phronesis), and scientific knowledge (episteme). Theoretical wisdom pertains to the understanding of fundamental truths about the world, while practical wisdom involves making sound judgments in everyday situations. Aristotle emphasizes that intellectual virtues are essential for achieving eudaimonia because they guide moral virtues, allowing individuals to make informed choices that align with their ultimate goals.

Aristotle asserts that both moral and intellectual virtues are necessary for a well-rounded character. A person who possesses moral virtues but lacks intellectual virtues may act ethically yet without understanding the deeper implications of their actions. Conversely, someone with intellectual virtues but lacking moral character may have the knowledge to make wise decisions but may not act upon it. The harmony between these two types of virtues is vital for achieving a fulfilling life.

Central to Aristotle's conception of virtue is the Doctrine of the Mean, which posits that virtue lies in finding a balanced approach between extremes of behavior. According to this doctrine, every moral virtue is a mean between two vices: one of excess and one of deficiency. This idea emphasizes moderation and the importance of context in ethical decision-making.

For example, consider the virtue of courage. Courage is the mean between the extremes of recklessness (excess) and cowardice (deficiency). A courageous person knows when to confront danger and when to exercise caution, demonstrating a balanced approach that leads to virtuous action. Similarly, the virtue of generosity is the mean between prodigality (excessive giving) and stinginess (deficiency in giving). In this way, the Doctrine of the Mean encourages individuals to cultivate a sense of moderation in their actions, leading to a more harmonious existence that contributes to eudaimonia.

The Doctrine of the Mean is not merely a formulaic approach to ethics; it requires practical wisdom (phronesis) to apply effectively. Different situations may call for different responses, and the virtuous individual must navigate these complexities with discernment. Aristotle acknowledges that achieving this balance is challenging, as it requires self-awareness, reflection, and an understanding of one’s own character. The practice of virtue, therefore, is an ongoing process of self-improvement and moral education.

Aristotle's emphasis on the mean highlights the dynamic nature of virtue. It is not a fixed state but rather a continual striving for balance in one’s life. This pursuit of virtue through moderation aligns with the overarching goal of eudaimonia, as it fosters a lifestyle that promotes overall well-being, ethical conduct, and meaningful relationships with others.

In summary, the role of virtue in achieving eudaimonia is foundational in Aristotelian ethics. Moral virtues shape our character and guide our actions, while intellectual virtues provide the necessary knowledge and judgment to navigate life’s complexities. The Doctrine of the Mean serves as a practical framework for understanding how to cultivate virtues effectively. By striving for balance and moderation, individuals can develop the character necessary for a flourishing life, ultimately leading to the fulfillment of their potential and the attainment of true happiness.

Key Points:In the realm of Aristotelian ethics, the concept of eudaimonia is intricately tied to the idea of the good life. It transcends mere happiness or transient pleasures, suggesting a deeper and more fulfilling existence that incorporates virtue, reason, and community. To fully comprehend the essence of eudaimonia, it is essential to explore its distinction from mere pleasure, the importance of relationships, and the broader implications it holds for living a meaningful life.

Aristotle makes a clear distinction between happiness (eudaimonia) and pleasure. While pleasure is often seen as an immediate, sensory experience that can be derived from various activities—such as eating, drinking, or engaging in leisure pursuits—happiness, in the Aristotelian sense, is a more profound state of being that encompasses the full realization of human potential. It is not merely about feeling good in the moment but rather living well and fulfilling one’s purpose.

In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that true happiness is an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue, and it is achieved over a lifetime through a series of virtuous actions. This contrasts sharply with the pursuit of pleasure, which can often lead to a hedonistic lifestyle that lacks depth and fulfillment. For Aristotle, the pursuit of pleasure alone may lead individuals astray, as it can distract them from the more significant goal of achieving eudaimonia through the cultivation of virtues.

Aristotle asserts that pleasure can accompany virtuous activities, but it is not the goal in and of itself. A person who engages in virtuous actions—such as acts of kindness, courage, and wisdom—may experience pleasure as a byproduct, yet the essence of their happiness lies in the fulfillment of their moral character and rational capabilities. Thus, eudaimonia is a holistic state of flourishing that integrates both rational thought and virtuous action.

The pursuit of eudaimonia is not an isolated endeavor; rather, it is deeply embedded within the context of community and relationships. Aristotle emphasizes the social nature of human beings, asserting that true happiness cannot be achieved in solitude. In his view, a complete life involves interactions with others, and these relationships are fundamental to the realization of eudaimonia.

Aristotle posits that individuals are inherently social creatures who seek companionship and community. This is reflected in his belief that a good life is one that is lived in accordance with others, where friendships and social bonds play a critical role. The importance of friendship, in particular, cannot be overstated. Aristotle categorizes friendships into three types: those based on utility, those based on pleasure, and those based on virtue. The highest form, virtuous friendship, is characterized by mutual respect, admiration, and a shared commitment to the good life.

In a community, individuals can support one another in their pursuit of eudaimonia. This collective aspect of happiness allows for the sharing of virtues, the exchange of ideas, and the reinforcement of moral character. For Aristotle, a flourishing community is one where individuals can develop their capacities fully, contributing to the common good while simultaneously enriching their own lives. The interdependence of individual well-being and communal flourishing underscores the Aristotelian view that eudaimonia is both a personal and collective journey.

Moreover, societal structures and norms play a significant role in shaping the conditions necessary for individuals to pursue eudaimonia. A just society, according to Aristotle, provides the framework within which individuals can cultivate their virtues and engage in meaningful relationships. Thus, the pursuit of eudaimonia is not only an individual endeavor but also a reflection of the health and moral character of the society in which one lives.

The interplay between virtue, community, and eudaimonia is crucial in understanding Aristotle's ethical framework. Virtue acts as the foundation upon which a good life is built, while community provides the environment necessary for the cultivation and practice of these virtues. In essence, the realization of eudaimonia is achieved through a synergistic relationship between the individual and their community, where virtues are nurtured and expressed through social interactions.

The development of virtues is often informed by the community’s ethical standards, which serve as a guide for individuals in their moral development. As individuals engage with their community, they learn from others, acquire new perspectives, and refine their understanding of what it means to live a good life. This reciprocal relationship highlights the importance of education and moral upbringing in the pursuit of eudaimonia.

Aristotle also emphasizes the role of laws and governance in facilitating the conditions necessary for eudaimonia. He argues that a well-ordered society promotes virtue among its citizens, allowing individuals to pursue their own happiness while contributing to the common good. In this light, the ethical responsibilities of individuals extend beyond personal development; they include a commitment to fostering a just and virtuous society that enables all members to seek their own eudaimonia.

In summary, the Aristotelian conception of eudaimonia is a rich and complex idea that encapsulates the essence of the good life. It transcends the superficial pursuit of pleasure, emphasizing the role of virtue, reason, and community in achieving true happiness. Aristotle’s insights into the nature of eudaimonia encourage individuals to reflect on their moral character, the significance of their relationships, and their responsibilities within the broader community.

Ultimately, eudaimonia serves as a guiding principle for ethical living, inviting individuals to engage in a continuous pursuit of virtue and to seek fulfillment through meaningful connections with others. In a world where the pursuit of pleasure often overshadows deeper aspirations, Aristotle's philosophy offers a timeless reminder of the importance of cultivating a life that is not only good for oneself but also for the greater community.

Aristotle’s notion of eudaimonia has sparked considerable debate and discussion among philosophers, ethicists, and scholars throughout history. This section explores the critiques and interpretations of eudaimonia, particularly focusing on modern perspectives and comparisons with other ethical theories.

In contemporary philosophy, Aristotle's concept of eudaimonia is often revisited in discussions regarding well-being and moral philosophy. Many modern philosophers have sought to reinterpret eudaimonia in light of current ethical challenges and understandings of human flourishing. Some notable perspectives include:

These varied interpretations and critiques highlight the evolving understanding of eudaimonia, demonstrating its relevance in contemporary ethical discussions.

Aristotle's eudaimonia is notably distinct from other ethical frameworks. Understanding these differences can illuminate the strengths and limitations of Aristotelian ethics in the broader context of moral philosophy. Key comparisons include:

| Ethical Theory | Core Principle | Relation to Eudaimonia |

|---|---|---|

| Utilitarianism | Maximizing overall happiness | Focus on collective outcomes rather than individual virtues |

| Deontological Ethics | Moral duty and adherence to rules | Emphasis on moral absolutes, potentially sidelining personal flourishing |

| Virtue Ethics (Modern) | Character and virtue as central to moral life | Aligns closely with Aristotelian ideas, emphasizing the importance of virtue in achieving eudaimonia |

| Care Ethics | Importance of relationships and care in moral decision-making | Broadens the understanding of eudaimonia to include social contexts |

These comparisons reveal how Aristotle's emphasis on virtue and character diverges from other ethical theories, which may prioritize outcomes or duties over the cultivation of personal virtues. Understanding these distinctions allows for a deeper appreciation of the multifaceted nature of ethics and the role of eudaimonia in shaping moral thought.

In summary, the critiques and interpretations of eudaimonia demonstrate the richness of Aristotelian ethics and its capacity to engage with a variety of philosophical perspectives. As modern thinkers continue to explore the implications of eudaimonia in contemporary life, Aristotle’s ideas remain a pivotal reference point in the ongoing discourse on ethics and human flourishing.