In the vast tapestry of human history, few cultures have woven narratives as rich and intricate as those of ancient Greece. At the heart of these stories lies a profound exploration of existence itself, a journey from the unfathomable depths of chaos to the intricate order of the cosmos. The Greeks crafted myths that not only entertained but also sought to explain the mysteries of the universe, reflecting their beliefs, values, and understanding of the world around them.

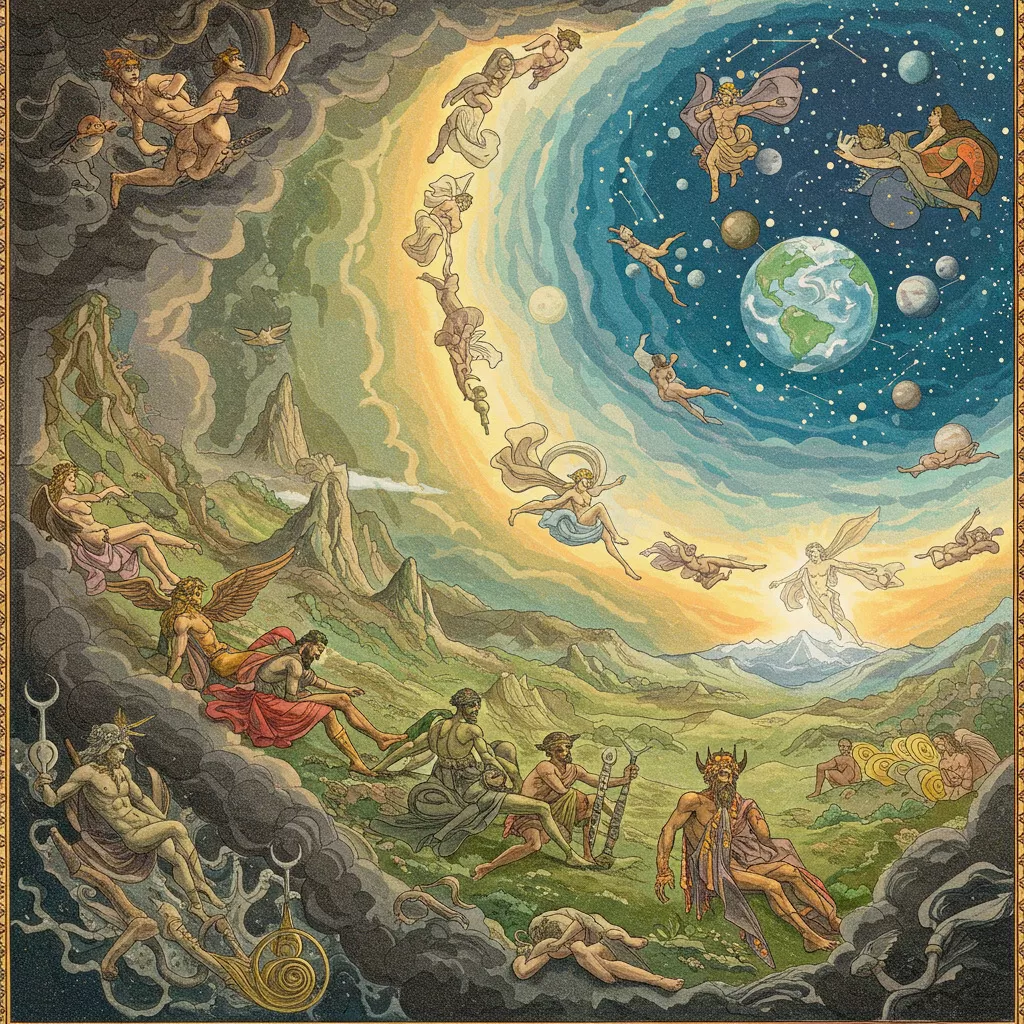

These creation narratives introduce us to primordial forces and deities who shaped the universe, giving birth to the earth and sky, and setting in motion a cosmic drama that would unfold over millennia. The emergence of powerful figures like Gaia and Uranus heralds the beginning of a lineage of gods and titans, each playing a pivotal role in the ongoing struggle between order and chaos. Through their tales, we witness the birth of not just the world, but also the fundamental principles that govern life and the human experience.

The stories of ancient Greece invite us to ponder the nature of divinity and humanity's place within the grand scheme of existence. As we delve into these myths, we uncover themes that resonate deeply with our own lives—creation and destruction, the quest for knowledge, and the eternal cycle of life and death. Each narrative serves as a mirror reflecting our aspirations, fears, and the timeless questions that continue to intrigue us, illuminating the path from chaos to a more harmonious cosmos.

Greek mythology is a rich tapestry of narratives that explain the origins of the world, the gods, and the human condition. At its core, it reflects the ancient Greeks' attempts to understand the universe and their place within it. The creation myths serve as foundational stories that illustrate how the cosmos transitioned from a state of chaos to a structured and ordered existence. These myths were not merely tales; they were integral to the cultural and religious fabric of ancient Greek society.

In ancient Greek cosmology, the concept of Chaos is paramount. Chaos is often described as a primordial void or a state of disorder that existed before anything else. According to Hesiod's "Theogony," one of the earliest sources on Greek mythology, Chaos was the first entity to emerge at the dawn of creation. This Chaos was not simply a vacuum; it was a formless, chaotic mixture of elements that lacked structure or definition.

Chaos is often personified as a deity in various interpretations of Greek mythology, representing the vastness and uncertainty of the universe. In this context, Chaos precedes the creation of the cosmos, embodying the potential from which all things arise. The transition from Chaos to order is depicted as a gradual process, emphasizing the importance of balance and harmony in the universe. This theme resonates throughout many creation myths, illustrating the ancient Greeks' belief in the necessity of order emerging from disorder.

Following the primordial Chaos, the next significant entities to emerge were Gaia (the Earth) and Uranus (the Sky). Gaia is often regarded as the mother of all life, representing fertility and nurturing, while Uranus symbolizes the vastness of the sky. Together, they form the foundation of the Greek cosmological structure.

According to Hesiod, Gaia produced Uranus from her own being, an act that signifies the interconnectedness of earth and sky. Their union led to the birth of the Titans, who would play a crucial role in the unfolding drama of Greek mythology. This creation myth highlights the significance of duality in the ancient Greek worldview, where opposites such as earth and sky coexist and interact to form the cosmos.

The relationship between Gaia and Uranus is complex, as it reflects themes of creation, conflict, and power. Uranus, fearing the potential power of his offspring, imprisoned them within Gaia's depths. This act of suppression led to significant consequences, including the eventual rebellion of the Titans against their father, which is a recurring theme in Greek mythology. The emergence of Gaia and Uranus marks a pivotal moment in the transition from chaos to an organized universe, and their story sets the stage for the subsequent generations of gods and titans.

The Titans, powerful deities in Greek mythology, played a pivotal role in the creation of the world and the subsequent establishment of the Olympian gods. As descendants of Gaia (the Earth) and Uranus (the Sky), the Titans represent an earlier generation of divine beings who contributed to the process of cosmic creation and order. Their narratives are rich in symbolism and reflect the ancient Greeks' understanding of the world around them, particularly regarding themes of power, rebellion, and the cyclical nature of existence.

The lineage of the Titans begins with the primordial deities, Gaia and Uranus. From their union, they birthed twelve original Titans, including Oceanus, Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Tethys, and Chronos. Each Titan held dominion over various aspects of the universe, embodying natural elements and fundamental concepts. For instance, Oceanus governed the ocean, while Hyperion represented light, illustrating how the Titans were intrinsically connected to the forces of nature.

As ancient Greek cosmology suggests, Uranus was not only the sky but also a tyrannical figure who imprisoned some of his children—the Cyclopes and the Hecatoncheires—within Gaia. This act incited Gaia's wrath, leading her to conspire with her son Cronus, the youngest of the Titans. Cronus eventually overthrew Uranus, symbolizing the transition from chaos to order, a recurring theme in Greek mythology. This act of rebellion established the Titans as the new ruling class of deities, further reshaping the cosmos.

The reign of the Titans marked a significant era characterized by their pursuit of power and the establishment of a more structured universe. However, their rule was not without conflict. The Titans' generation set the stage for the rise of the Olympians, particularly as Cronus's fear of being overthrown led him to consume his children. This cycle of power and fear illustrates the complex dynamics within the divine hierarchy of Greek mythology.

Among the Titans, Prometheus stands out as a central figure in creation myths, particularly for his act of defiance against the established order. Known for his intelligence and cunning, Prometheus is credited with the creation of humanity and the gift of fire. His story highlights the themes of sacrifice, rebellion, and the relationship between gods and mortals.

According to myth, after Cronus was overthrown by Zeus, the new king of the gods sought to maintain control over humanity. Prometheus, however, sympathized with humans, whose existence was marked by hardship and suffering. In an act of rebellion, Prometheus stole fire from Olympus and gifted it to humanity, enabling them to progress and evolve. This act not only illuminated the physical world but also symbolized enlightenment and knowledge, essential for human civilization.

Despite his noble intentions, Prometheus's actions incurred the wrath of Zeus, who viewed the gift of fire as a direct challenge to his authority. As punishment, Zeus had Prometheus bound to a rock where an eagle would eat his liver daily, only for it to regenerate overnight, ensuring his eternal suffering. This punishment underscores the tension between divine authority and the pursuit of knowledge, a fundamental theme in Greek mythology.

Prometheus's story resonates on multiple levels. It reflects the human quest for knowledge and progress and raises questions about the moral implications of defiance against authority. His suffering also serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of one's actions, particularly when challenging the gods.

The Titans' rule came to an end with the rise of the Olympians, leading to a cataclysmic conflict known as the Titanomachy. This war marked the transition from the age of Titans to the reign of the Olympian gods, a significant shift in the Greek mythological narrative. Zeus, along with his siblings—Hestia, Hera, Demeter, Poseidon, and Hades—led the charge against Cronus and the other Titans to reclaim power over the cosmos.

The Titanomachy lasted for ten years, during which the Olympians faced formidable opposition from the Titans, who were determined to maintain their rule. The war was characterized by epic battles, cunning strategies, and divine interventions. Ultimately, the Olympians emerged victorious, with Zeus using his thunderbolts to overthrow the Titans. This victory not only solidified the Olympians' dominance but also ushered in a new cosmic order, establishing Zeus as the supreme deity.

The aftermath of the Titanomachy saw the defeated Titans imprisoned in Tartarus, a deep abyss in the Underworld, symbolizing their fall from grace and the establishment of a new divine hierarchy. The conflict between the Titans and the Olympians represents the classic theme of generational struggle, illustrating how the old order must yield to the new in the pursuit of balance and stability within the cosmos.

The legacy of the Titans extends beyond their immediate role in creation myths. They embody the duality of creation and destruction, order and chaos, contributing to the rich tapestry of Greek mythology. Their narratives serve as cautionary tales about power dynamics, the consequences of rebellion, and the cyclical nature of existence.

In many ways, the Titans can be seen as archetypal figures representing the struggles inherent in human experience. Their stories resonate with themes of ambition, conflict, and the complex relationship between authority and autonomy. As humanity grapples with its own challenges, the lessons derived from the Titans' narratives continue to hold relevance, offering insights into the eternal quest for balance and understanding in a world that oscillates between chaos and order.

In conclusion, the Titans are essential figures in the creation myths of Ancient Greece, representing the foundation upon which the Olympian gods would build their reign. Their stories illustrate the complexities of power, the nature of rebellion, and the transformative journey from chaos to cosmos. Through their narratives, the ancient Greeks articulated their understanding of the world and the forces that shaped their existence, leaving a lasting legacy that continues to captivate and inspire.

The creation myths of Ancient Greece are filled with a rich tapestry of gods and goddesses who played pivotal roles in shaping the cosmos. While the initial chaos gave way to order through the emergence of primordial deities like Gaia and Uranus, it was the subsequent generation of gods and goddesses who would ultimately govern the universe. This section delves into the significance of Zeus as the king of the gods and explores the dynamic relationships within the Olympian pantheon.

Zeus, the chief deity of the Greek pantheon, embodies the principles of order and justice. Born to the Titans Cronus and Rhea, Zeus was destined to overthrow his father, who had swallowed his siblings to prevent them from usurping his throne. Rhea, determined to save her youngest child, hid Zeus in a cave on the island of Crete and presented Cronus with a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes instead.

Zeus's rise to power is marked by a series of significant events that highlight his strength and cunning. After reaching adulthood, he freed his siblings—Hestia, Hera, Demeter, Poseidon, and Hades—from Cronus's belly, and together they waged a ten-year war against the Titans, known as the Titanomachy. This monumental conflict resulted in the defeat of the Titans and the establishment of Zeus as the supreme ruler of the gods.

Once in power, Zeus became synonymous with the sky, thunder, and lightning. He wielded a mighty thunderbolt, symbolizing his authority and ability to enforce justice. His character is complex; while he is often seen as a protector of order, he also embodied the capricious nature of power. Zeus's numerous affairs with goddesses and mortals led to the birth of many demi-gods and heroes, further complicating his legacy.

Zeus's role as a ruler extends beyond mere might; he is also a figure of moral authority. The ancient Greeks revered him as a god of hospitality and oaths, and many rituals and offerings were dedicated to ensure his favor. Temples, such as the magnificent Temple of Zeus at Olympia, were erected in his honor, where the Olympic Games were held every four years as a tribute to the king of the gods.

The Olympian pantheon comprises twelve principal deities who reside on Mount Olympus, symbolizing the pinnacle of power and influence in the Greek mythological landscape. These gods and goddesses personified various aspects of life, nature, and human experience, each playing a unique role in the mythology and worship of Ancient Greece.

Aside from Zeus, the principal deities of the Olympian pantheon include:

The relationships among these deities are complex, filled with rivalries, alliances, and familial ties that shape the narratives of Greek mythology. For example, the tension between Hera and Zeus often leads to dramatic conflicts, while the sibling rivalry between Athena and Poseidon over the patronage of Athens reflects the competition for power and influence among the gods.

The myths surrounding the Olympians not only illustrate their individual attributes and stories but also serve as allegories for human experiences. The deities embody qualities and flaws that resonate with the ancient Greeks, making them relatable figures in a world often filled with unpredictability. Worship of these gods was an integral part of Greek society, influencing festivals, rituals, and daily life.

The ancient Greeks built grand temples and altars dedicated to their deities, with elaborate ceremonies performed to honor them. Festivals such as the Panathenaea in Athens celebrated Athena, while the Dionysia honored Dionysus with dramatic performances and revelry. These events reinforced the connection between the gods and the people, emphasizing the belief that the favor of the deities was crucial for prosperity and success.

In addition to temples and festivals, the artistic representation of the gods played a significant role in Greek culture. Sculptures, pottery, and paintings often depicted the gods in human form, showcasing their divine attributes and stories. This artistic expression served to immortalize their myths and reinforce their significance in the cultural consciousness of Ancient Greece.

Overall, the Olympian pantheon represents the culmination of Greek mythology, where gods and goddesses not only govern the cosmos but also reflect the values and beliefs of the society that worships them. Their stories, filled with intrigue, conflict, and moral lessons, continue to captivate audiences today and offer insights into the human condition.

Creation myths serve as foundational narratives that explain the origins of the world and humanity. In the context of Ancient Greece, these myths are rich with symbolism and profound themes that reflect the values, beliefs, and cultural identity of the Greek people. Central to these narratives are the concepts of order versus chaos and the cycle of life and death, both of which are intricately woven into the fabric of Greek mythology.

The dichotomy of order and chaos is a recurring theme in Greek creation myths, which can be traced back to the very beginnings of the cosmos. In the primordial chaos, a formless void existed before the emergence of anything recognizable. This chaos symbolizes not just disorder, but also potentiality—the possibility of creation. It is from this chaotic state that the first deities emerged, marking the transition from chaos to order.

Gaia, the Earth, represents the first step toward order. She is often depicted as a nurturing mother, embodying fertility and stability. In contrast, her counterpart, Uranus (the sky), signifies the expansive and sometimes unpredictable nature of the heavens. Their union represents the first harmonious order in the cosmos. The offspring of Gaia and Uranus, the Titans, further illustrate this theme of order emerging from chaos. However, their subsequent actions eventually lead to a new chaos, as they engage in power struggles that unsettle the cosmos once more.

One of the most significant events in this struggle for order is the Titanomachy, the great war between the Titans and the Olympian gods. This conflict exemplifies the ongoing battle between established order and the chaos that arises from rebellion and ambition. The victory of the Olympians, led by Zeus, signifies the establishment of a new cosmic order, yet it also highlights the cyclical nature of chaos and order—one cannot exist without the other. The myths convey a message that while order can be achieved, it is often precarious and must be defended against the forces of chaos, both external and internal.

The cycle of life and death is another fundamental theme in Greek mythology, reflecting the natural rhythms observed in the world. This theme is particularly evident in the myths surrounding the gods and their relationships with humanity. The Greeks understood life as a series of cycles—birth, growth, decay, and renewal—mirroring the agricultural cycles that governed their lives.

In the myth of Demeter and Persephone, we see a powerful representation of this cycle. Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, experiences profound grief when her daughter Persephone is abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld. This event triggers the cycle of the seasons: when Persephone is with Hades, the earth becomes barren, symbolizing winter and death. However, when she returns to her mother in the spring, life is restored, and the earth flourishes once more. This myth not only illustrates the cycle of life and death but also emphasizes the interconnectedness of nature and the divine.

Furthermore, the Greeks believed in a form of immortality through legacy, as seen in the stories of heroes who achieve great deeds and are remembered through myth and song. The idea that one could achieve a form of eternal life through honor and remembrance reflects the human desire to transcend mortality. This theme resonates deeply in the stories of figures like Heracles and Achilles, whose exploits ensure their place in the pantheon of heroes long after their physical deaths.

The symbolism present in these myths extends beyond mere narrative; it serves as a lens through which the Greeks understood their world and themselves. For instance, the imagery of light and darkness often symbolizes knowledge and ignorance, respectively. The emergence of light from chaos represents enlightenment and the establishment of order, while the return to chaos signifies ignorance and disorder.

Additionally, the representations of various deities embody different aspects of the human experience. For example, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and warfare, symbolizes the balance between intellect and brute force. Her birth from Zeus's forehead, fully formed and armored, underscores the idea that wisdom and strategy are paramount in achieving success, especially in the context of conflict. Conversely, Dionysus, the god of wine and revelry, represents the chaotic and primal aspects of human nature. His duality embodies the tension between civilization and the untamed instincts that lurk within.

This interplay between order and chaos, life and death, and the multifaceted nature of the gods reflects the complexity of the human condition. The myths serve as both a mirror and a guide, illustrating the struggles and triumphs that define existence. They invite contemplation on the nature of power, the consequences of hubris, and the inevitability of change.

Through the exploration of these themes, Greek creation myths provide not only a narrative of the cosmos's origins but also a profound philosophical framework for understanding the world. The tension between order and chaos remains relevant today, as societies continue to grapple with maintaining stability in the face of uncertainty. Similarly, the cycle of life and death resonates deeply in contemporary discussions about mortality, legacy, and the human experience.

Ultimately, the rich symbolism and themes embedded in Greek mythology continue to captivate audiences, inviting them to reflect on their own lives and the world around them. As we delve into these ancient stories, we uncover timeless truths that transcend the boundaries of time and culture, reminding us of our shared humanity and the eternal quest for understanding our place in the cosmos.