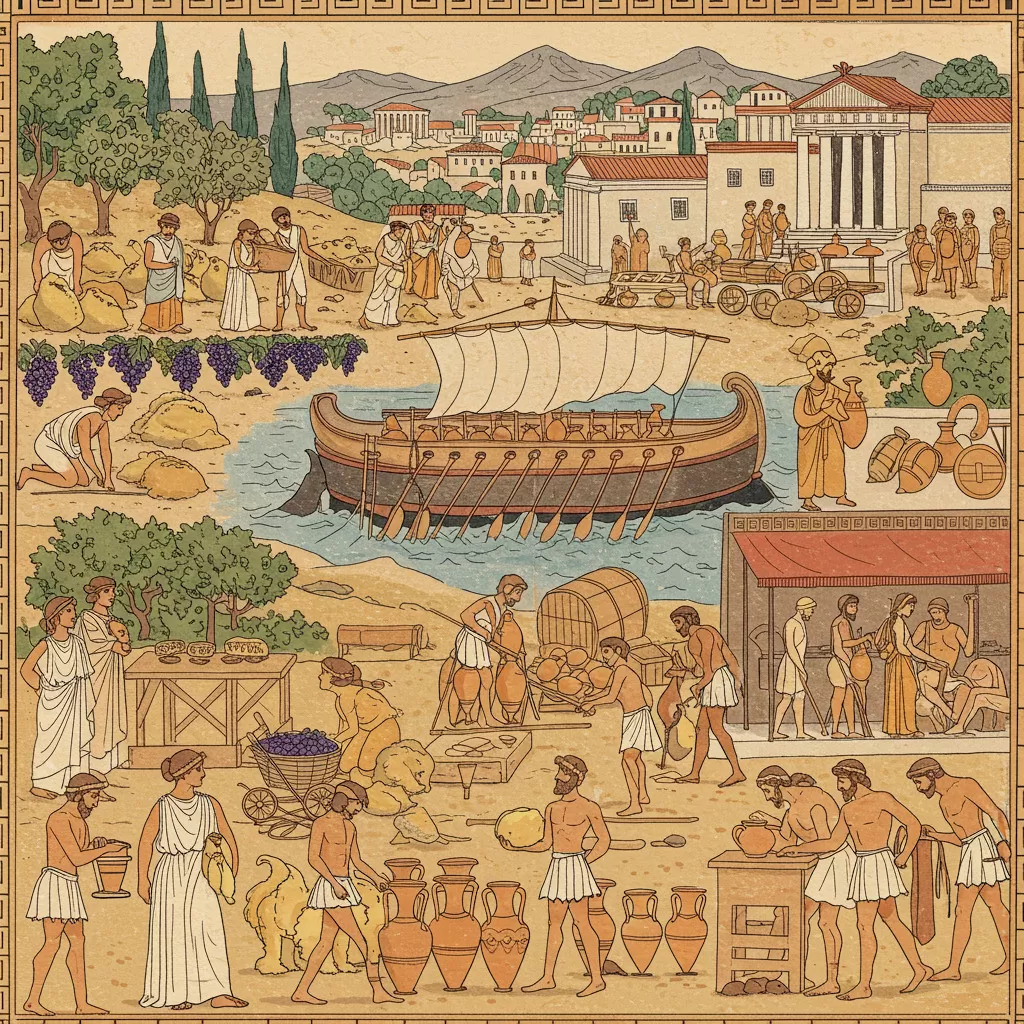

The ancient Greek world, steeped in a rich tapestry of history and culture, was profoundly shaped by its intricate trade networks and economic practices. As city-states flourished along the Aegean Sea, they engaged in commerce that not only facilitated the exchange of goods but also fostered connections among diverse cultures. This dynamic environment laid the groundwork for the development of an economy that would influence the region for centuries to come.

Geographical advantages played a crucial role in the establishment of trade routes, enabling access to valuable resources and fostering relationships with neighboring civilizations. The bustling agoras became the heart of economic activity, where merchants and citizens alike participated in a vibrant exchange of commodities, ideas, and innovations. The evolution of trade practices, from barter systems to the nascent use of currency, reflected the adaptability and ingenuity of the Greek people in navigating the complexities of their economy.

However, the landscape of trade was not solely determined by economic factors; it was also shaped by socio-political elements. The interplay between individual city-states and their economic policies, as well as the ever-present threat of warfare, influenced trade dynamics and created a mosaic of opportunities and challenges. Ultimately, the cultural impact of trade on Greek society cannot be overstated, as it served as a conduit for the spread of ideas, art, and religious practices, weaving an intricate connection between commerce and the very fabric of ancient Greek life.

The Archaic period of Greece, spanning from approximately the 8th to the 6th centuries BCE, marked a significant transformation in the social, political, and economic fabric of Greek society. This era was characterized by the rise of city-states, the establishment of colonies, and the expansion of trade networks that connected the Greek world with various regions across the Mediterranean and beyond. The historical context of trade during this period is crucial to understanding how it shaped the emerging Greek economy and society.

Geography played a pivotal role in shaping trade in Archaic Greece. The region's mountainous terrain and numerous islands created natural barriers, leading to the development of independent city-states, each with its own unique resources and trade needs. The Mediterranean Sea served as a vital highway for commerce, connecting different cultures and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies.

Major trade routes emerged along the coasts, with important ports such as Corinth, Athens, and Aegina becoming bustling centers of economic activity. The proximity to fertile lands in regions like Boeotia and Thessaly provided agricultural products, while the islands, particularly the Cyclades, became important for maritime trade due to their strategic locations. Furthermore, the trade routes extended not only across the Mediterranean but also into the Black Sea, where Greeks established colonies such as Byzantium and Olbia, further enhancing their access to grain and other valuable commodities.

During the Archaic period, Greek trade was characterized by a diverse array of commodities that reflected the region's agricultural and artisanal output as well as the needs of its trading partners. Key trade partners included the Near East, Egypt, and the Italian peninsula. The Greeks exported olive oil, wine, pottery, and textiles, while importing essential goods such as grain, metals, and luxury items.

Grain, particularly from the Black Sea region, was crucial for the sustenance of the growing population in the city-states. The export of olive oil, a staple of the Mediterranean diet, not only contributed to the economy but also played a significant role in trade relationships, as it was highly valued across various cultures. Pottery, with its intricate designs and practical uses, became a symbol of Greek craftsmanship and was widely traded, showcasing the artistry and culture of the time.

This exchange of goods facilitated not only economic prosperity but also cultural interactions that enriched Greek society, laying the groundwork for the flourishing of art, philosophy, and science in the subsequent Classical period.

The economic landscape of Archaic Greece, spanning roughly from the 8th to the 6th centuries BCE, was a complex interplay of various structures and practices that shaped its development. Central to the evolution of this economy were the systems of trade, the mechanisms of exchange, and the sociopolitical frameworks in which these interactions occurred. The transition from a primarily barter-based economy to one increasingly influenced by currency and market practices marks a significant shift in ancient Greek society. This section delves into the nuances of these economic structures, exploring the barter system versus currency use and the pivotal role of agoras as centers of economic activity.

In the earliest phases of Archaic Greece, trade was primarily conducted through a barter system, which involved the direct exchange of goods and services without a standardized medium of exchange. This system was prevalent due to the localized nature of early Greek economies, where communities often relied on their immediate resources and produced goods for trade. For instance, a farmer might exchange a surplus of grain for pottery or livestock produced by a neighboring artisan. Such exchanges were typically based on mutual needs and relationships, fostering community ties and dependencies.

However, as trade expanded beyond local boundaries, the limitations of the barter system became increasingly apparent. The need for a more efficient medium of exchange prompted the gradual introduction of currency. The earliest forms of currency in Greece were often made from valuable metals such as bronze, silver, and gold, which were shaped into coins. The use of coins revolutionized trade by providing a standardized unit of value that could facilitate transactions across different regions. This transition was not uniform and varied significantly among city-states.

The introduction of coinage is often attributed to the Lydians in the 7th century BCE, but Greek city-states quickly adopted and adapted this practice. By the 6th century BCE, cities like Athens and Corinth began minting their own coins, which became vital for commerce. The Athenian silver drachma, for example, became a dominant currency in trade, reflecting the city's economic power and influence across the Mediterranean. This shift toward currency not only streamlined trade practices but also allowed for greater investment in various sectors, including agriculture, craftsmanship, and maritime activities.

Agoras played a crucial role in the economic structures of Archaic Greece, serving as public gathering spaces where various aspects of daily life converged, particularly commerce and trade. The term "agora" itself translates to "gathering place," and these marketplaces were vital for facilitating economic transactions, social interactions, and political discourse among citizens. Each city-state typically had its own agora, which was strategically located at the heart of the urban landscape, making it accessible to the populace.

In the agora, merchants and artisans showcased their goods, ranging from agricultural products to crafted items. The presence of diverse commodities fostered a vibrant marketplace where buyers and sellers could negotiate prices, often using currency or bartering as means of exchange. The agora also served as a hub for information exchange, where news and ideas could spread rapidly among citizens, reflecting the interconnected nature of economic and social life in Archaic Greece.

Beyond trade, agoras were integral to the political fabric of Greek society. Many significant civic activities took place in these spaces, including public assemblies, religious ceremonies, and cultural festivities. The agora thus functioned not only as an economic center but also as a symbol of civic identity and participation. The interaction between trade and civic life was profound; economic prosperity often translated into political power, allowing wealthier citizens to exert greater influence over decision-making processes within their city-states.

In examining the role of agoras, it is essential to recognize their impact on the development of urban centers. As trade flourished, agoras attracted larger populations, prompting the growth of cities and the establishment of more complex social hierarchies. This urbanization facilitated the specialization of labor, as individuals could focus on specific trades or crafts, enhancing overall productivity and economic output.

Moreover, the agora's significance extended to cultural exchanges, as merchants and travelers from various regions brought with them not only goods but also new ideas, technologies, and practices. This cultural diffusion was instrumental in shaping various aspects of Greek life, from artistic expression to philosophical thought, highlighting the intricate relationship between economic practices and cultural development.

In summary, the economic structures and practices of Archaic Greece were characterized by the evolution from a barter system to the adoption of currency, with agoras serving as critical centers for trade and social interaction. This dynamic contributed to the economic prosperity of city-states, facilitating not only the exchange of goods but also the flow of ideas and cultural practices that would leave a lasting impact on Greek society. The legacy of these early economic practices laid the groundwork for the more complex economies that would emerge in Classical Greece and beyond.

The intertwining of trade and politics in Archaic Greece is a complex tapestry that reveals much about the societal dynamics of the time. The period, roughly spanning from the 8th century to the early 5th century BCE, witnessed the rise of city-states, known as poleis, which played a pivotal role in shaping economic structures and trade practices. This section delves into the socio-political factors that significantly influenced trade, focusing on the economic policies of city-states and how warfare impacted trade dynamics.

The city-state was the fundamental political unit of ancient Greece, and each polis had its unique economic policies that dictated trade practices. The most prominent city-states, such as Athens, Corinth, and Sparta, developed distinct approaches to trade that not only reflected their political ideologies but also their economic needs and resources.

Athens, for instance, emerged as a powerful trade hub due to its strategic location and maritime prowess. The Athenian economy heavily relied on trade, as the city lacked sufficient agricultural land to sustain its growing population. Consequently, Athens established a network of trade routes across the Mediterranean, exporting goods like olive oil, pottery, and wine, while importing grain, timber, and luxury items. The Athenian government actively supported trade through the establishment of favorable laws and the expansion of its navy, which safeguarded merchant vessels against piracy and ensured the safe passage of goods.

Corinth, on the other hand, thrived on its strategic position between the Peloponnese and mainland Greece, controlling trade routes across the Isthmus of Corinth. The city-state was known for its rich resources of pottery and textiles, which became significant exports. Corinthian economic policies included the encouragement of trade through the establishment of colonies, which served as extensions of their commercial empire. These colonies were established in key locations, facilitating further trade and cultural exchange.

In contrast, Sparta's approach to trade was markedly different. Known for its militaristic society and emphasis on self-sufficiency, Sparta was less reliant on trade compared to its counterparts. The Spartans focused on agriculture and maintained a strict social order that prioritized military training over commerce. However, the need for luxury goods and resources led to a regulated form of trade, where the state controlled economic activities to ensure that Spartan citizens remained focused on their military duties. This economic policy had profound implications, limiting the scope of trade and commercial engagement.

The policies of these city-states were not only influenced by their internal needs but also by external pressures, such as alliances, conflicts, and competition with rival city-states. Trade was often used as a tool for diplomacy, with cities forming alliances based on mutual economic interests. Conversely, economic competition could lead to tensions and conflicts, as evidenced by the Peloponnesian War, which significantly impacted trade routes and economic stability in the region.

Warfare in Archaic Greece had profound implications for trade dynamics, often reshaping economic landscapes and altering trade routes. The period was marked by frequent conflicts between city-states, which not only disrupted trade but also prompted changes in political alliances that could affect economic practices.

During times of war, the security of trade routes became a paramount concern. The Athenian navy, for example, played a crucial role in protecting merchant vessels from piracy and enemy attacks. However, when conflicts arose, such as during the Persian Wars or the Peloponnesian War, trade routes could be severely disrupted, leading to economic hardship. The blockade of ports, destruction of trade vessels, and diversion of military resources often resulted in a decline in trade activity.

Moreover, warfare also influenced the types of goods traded. During conflicts, certain commodities became more valuable, such as weapons, armor, and provisions. City-states that produced these goods often found themselves in advantageous positions, able to leverage their resources for economic gain. Conversely, regions that suffered from warfare faced scarcity and economic decline, as agricultural production and trade were disrupted.

The aftermath of warfare often led to a reconfiguration of trade networks. For instance, following the Peloponnesian War, the power dynamics shifted in favor of Sparta, altering existing trade routes and alliances. The defeat of Athens meant that its extensive trade network was curtailed, leading to a decline in Athenian influence over Mediterranean trade. In contrast, Spartan dominance led to the establishment of new economic policies that emphasized military strength over trade, reshaping the region's economic landscape.

Additionally, the effects of warfare on trade extended beyond immediate economic consequences. The experiences of conflict also influenced cultural exchanges and the spread of ideas, as displaced populations sought new opportunities in different city-states or regions. This movement of people often facilitated the exchange of goods and cultural practices, further intertwining trade with the socio-political fabric of Greek society.

Trade and economic practices in Archaic Greece were deeply intertwined with the socio-political landscape of the time. The policies adopted by city-states not only shaped their economic activities but also reflected broader political ideologies and alliances. Furthermore, warfare significantly impacted trade dynamics, altering routes, influencing the types of goods exchanged, and reshaping economic relationships among the city-states. Understanding these socio-political factors provides valuable insights into the complexities of trade in ancient Greece and its enduring legacy on subsequent civilizations.

Key Points:The economic landscape of Archaic Greece was not merely a series of transactions; it was a complex web of interactions that facilitated the exchange of ideas, culture, and social practices. Trade was a catalyst for cultural development during this period, profoundly influencing Greek society in various dimensions. From the spread of ideas and innovations to the evolution of art and religious practices, trade served as a conduit through which the cultural identity of the Greeks was shaped and transformed.

One of the most significant cultural impacts of trade in Archaic Greece was the dissemination of ideas. As Greek merchants and traders traveled to distant lands, they encountered diverse cultures, philosophies, and customs. This exposure led to the adoption and adaptation of various elements that enriched Greek intellectual and social life.

For example, interactions with the Near East, particularly through trade routes linking Greece with regions like Anatolia and Phoenicia, introduced the Greeks to new technologies, agricultural practices, and artistic styles. The Phoenicians, known for their seafaring abilities and advanced trade networks, played a crucial role in facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas. The adoption of the Phoenician alphabet around the 8th century BCE is a prime example of how trade led to significant intellectual advancements. This adaptation not only simplified writing but also helped in the preservation and transmission of Greek literature and philosophy, shaping the intellectual landscape for centuries to come.

Furthermore, the exchange of religious ideas and practices was also notable. The Greeks encountered various deities and religious customs through their trading connections, particularly with Egypt and the Near East. The incorporation of foreign gods into the Greek pantheon exemplifies how trade fostered a syncretic approach to religion. The worship of deities such as Isis and Osiris became popular in certain Greek city-states, reflecting the influence of trade on spiritual life.

The artistic expressions of Archaic Greece were also shaped significantly by trade. The influx of new materials and techniques from abroad allowed Greek artisans to explore innovative forms and styles. For instance, the introduction of luxury goods such as imported pottery, textiles, and metals influenced local art forms, leading to the development of unique styles that blended local traditions with foreign influences.

Trade routes facilitated the exchange of artistic ideas between Greece and its trading partners. The production of black-figure and red-figure pottery, for instance, saw a significant evolution as artisans incorporated techniques and motifs from Eastern Mediterranean cultures. The geometric patterns that characterized early Greek pottery began to give way to more elaborate representations of human figures and mythological scenes, showcasing a growing sophistication in artistic expression.

Religious practices were similarly impacted by trade. The Greeks not only spread their own religious practices but also adopted elements from other cultures. Temples dedicated to foreign gods were constructed, and festivals celebrating these deities became commonplace. The expansion of trade led to the establishment of panhellenic sanctuaries, such as the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, where traders and pilgrims would gather, further promoting the exchange of religious and cultural ideas.

Trade also played a pivotal role in the economic integration of various Greek city-states. As different regions began to rely on each other for specific goods—such as grain from the Black Sea region, olive oil from Attica, and pottery from Corinth—a network of economic interdependence emerged. This situation contributed to a sense of shared identity among the Greeks, transcending regional differences and fostering a collective cultural consciousness.

The establishment of trade colonies, such as those founded in Sicily and the southern coast of Italy, further illustrated this phenomenon. These colonies not only served as commercial outposts but also as cultural hubs where Greek traditions mingled with local customs. The result was a vibrant exchange that enriched both Greek and local cultures, leading to the spread of Hellenistic ideals and practices.

While trade fostered cultural exchange, it also exposed and sometimes exacerbated social stratification within Greek society. Wealth generated from trade and commerce often accumulated in the hands of a select few, leading to a growing divide between the affluent merchant class and the agrarian poor. This economic disparity influenced social dynamics, contributing to tensions that would later manifest in political movements and changes in governance structures.

The rise of the wealthy elite, often referred to as the "new aristocracy," brought about shifts in cultural norms. Their patronage of the arts and public works, funded by the profits of trade, led to a flourishing of cultural achievements. However, it also created a culture of competition among the elite, where status was measured not only by lineage but also by wealth and influence derived from trade.

Trade was not without its conflicts. The competition for control over lucrative trade routes and resources often led to warfare between city-states. The Peloponnesian War, for instance, had significant economic motivations rooted in trade rivalries. Such conflicts could disrupt trade, impacting the flow of goods and ideas and leading to cultural isolation for some city-states.

Despite these conflicts, the aftermath of wars often resulted in the sharing of cultural practices and ideas. Following conquests, victors would frequently adopt elements of the conquered culture, leading to a blending of traditions. The influence of warfare on trade dynamics created a complex interplay that shaped the cultural landscape of Greece, reinforcing the notion that trade was as much about cultural exchange as it was about economic gain.

In summary, the cultural impact of trade on Greek society during the Archaic period was profound and multifaceted. Through the spread of ideas, artistic innovation, religious exchange, economic integration, and social stratification, trade facilitated a dynamic cultural environment that greatly influenced the development of Hellenic identity. The legacy of this period continues to resonate in the cultural and historical narratives of Greece, serving as a reminder of the intricate connections between commerce and culture.

Key Points: