The Archaic Period of ancient Greece stands as a fascinating epoch where religion and rituals intertwined seamlessly with daily life, shaping the very fabric of society. As communities evolved, so too did their beliefs, giving rise to a pantheon of deities and mythological narratives that not only explained the world around them but also guided their moral and ethical frameworks. This period witnessed a profound reverence for the divine, as people sought to understand their existence through the lens of spirituality and communal worship.

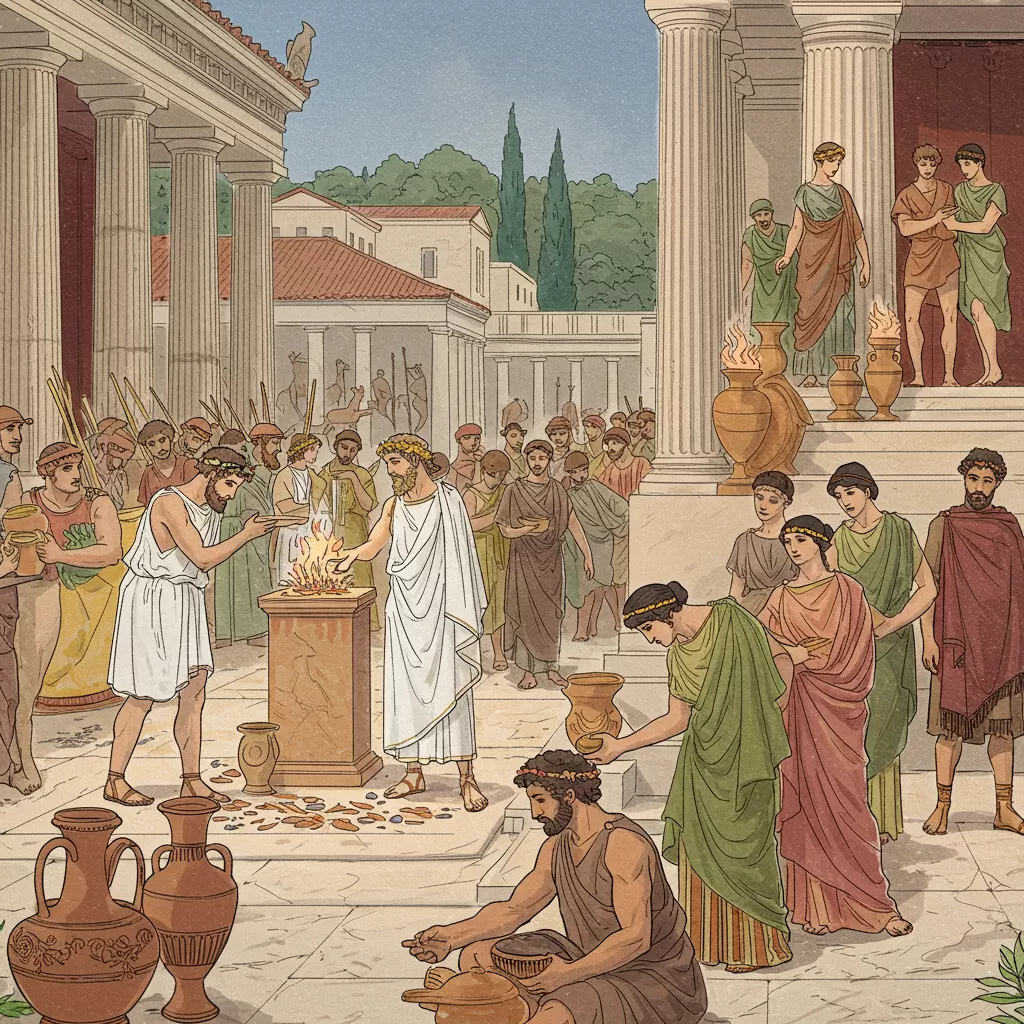

Ritual practices played a pivotal role in reinforcing social bonds and cultural identity, as they were intricately tied to agricultural cycles, seasonal changes, and key life events. From sacrificial offerings that honored the gods to vibrant festivals that brought communities together, these ceremonies were more than mere observances; they were essential expressions of gratitude and devotion. The significance of these rituals resonated deeply, leaving an indelible mark on the collective psyche of the Greek people.

Moreover, the geographical landscape of ancient Greece profoundly influenced the nature of religious practices. Local cults flourished, each with unique customs and deities that reflected the diverse identities of the city-states. Sacred sites emerged as focal points of worship, where the faithful gathered to seek favor and blessings from the divine. Through archaeological evidence, we can piece together the rich tapestry of these beliefs, revealing how religion and rituals were not only central to individual lives but also to the broader narrative of ancient Greek civilization.

The Archaic Period of ancient Greece, spanning roughly from the eighth to the sixth centuries BCE, marks a transformative time in the development of Greek culture, including its religious practices and beliefs. During this era, the foundations of what would later become classical Greek religion were laid, characterized by a rich tapestry of myths, deities, and rituals that shaped the everyday lives of the people. Understanding the landscape of religion and its significance during this period involves delving into the major beliefs and deities worshiped, as well as the profound role of mythology in daily life.

Religious beliefs in the Archaic Period were polytheistic, with a pantheon of gods and goddesses who were believed to control various aspects of nature and human life. The Greeks worshipped a multitude of deities, each associated with different domains, such as agriculture, warfare, love, and the sea. Among the most prominent deities was Zeus, the king of the gods, who reigned over Mount Olympus. His authority and power were often invoked in various aspects of life, from politics to personal affairs.

Other significant figures included Hera, Zeus's wife and goddess of marriage and family; Athena, goddess of wisdom and warfare; Apollo, god of music and prophecy; and Demeter, goddess of agriculture. Each deity had specific attributes and responsibilities, and they were often depicted in art and literature, which further reinforced their importance in society. Worship of these gods was not merely a form of reverence but a way to ensure favor and avert calamity, highlighting the belief in the divine's direct influence on earthly affairs.

In addition to the major Olympian gods, local deities and heroes also played a significant role in religious practices. Each city-state had its patron god or goddess, such as Athena for Athens and Poseidon for Corinth, which fostered a strong sense of local identity and pride. This localized worship was often accompanied by unique myths and stories that celebrated the deeds of these deities and emphasized their connection to the city's history and values.

Mythology served as a vital framework through which the Greeks understood their world. Myths provided explanations for natural phenomena, human behavior, and the origins of their customs and rituals. They were not merely fanciful tales but were interwoven into the very fabric of Archaic society, influencing art, literature, and philosophy. The narratives surrounding the gods and heroes conveyed moral lessons, social norms, and cultural values that were essential for maintaining order and cohesion within the community.

Daily life in the Archaic Period was permeated by religious observance. Rituals and myths were invoked in various circumstances, from agricultural practices to family matters. For instance, the myth of Demeter and Persephone illustrated the changing seasons and was reflected in agricultural festivals such as the Thesmophoria, which celebrated fertility and the harvest. Similarly, the story of Odysseus and his adventures not only entertained but also served as a moral compass for individuals navigating the complexities of honor, loyalty, and perseverance.

Moreover, mythology was a crucial component of education for the youth, who were taught these stories as part of their cultural heritage. The oral tradition of storytelling allowed these myths to be passed down through generations, ensuring that the values and beliefs of the Archaic Period were preserved and adapted over time. This connection between mythology and daily life underscored the significance of religion as a guiding force in the lives of the ancient Greeks.

In summary, the Archaic Period was a formative time for Greek religion, characterized by a rich pantheon of deities and a mythology that deeply influenced daily life. The major beliefs and deities worshiped during this period laid the groundwork for the more complex religious practices that would emerge in later centuries. This understanding of religion in the Archaic Period not only highlights the significance of divine beings in ancient Greek culture but also emphasizes the integral role of mythology in shaping the values and beliefs of society.

The Archaic Period of Ancient Greece, roughly spanning from the 8th to the 6th centuries BCE, was a time of significant social and cultural transformation. As Greek city-states began to form and develop their unique identities, religious practices and rituals played a central role in the lives of the people. These practices not only reflected the deep-seated beliefs of the society but also served to unify communities and reinforce social hierarchies. Understanding the ritual practices and ceremonies of this period provides insight into the spiritual and communal life of ancient Greeks.

Sacrifice was a fundamental aspect of religious practice in the Archaic Period. The Greeks believed that their gods required offerings to maintain favor and ensure prosperity. Sacrificial offerings were not merely acts of devotion; they were complex rituals that involved the entire community. Animals, such as sheep, goats, and cattle, were the most common offerings, and the choice of the animal often depended on the deity being honored.

The significance of sacrificial offerings can be understood in several dimensions. Firstly, they were a means of communication with the divine. By offering something valuable, the worshippers sought to appease the gods and gain their protection and blessings. Secondly, sacrifices served as a social function, bringing communities together in worship and celebration. Major festivals often included public sacrifices that reinforced communal bonds and provided a sense of shared identity.

For example, the Panathenaic Festival in Athens featured grand sacrifices of cattle to Athena, the city's patron goddess. This festival not only showcased the city's wealth and piety but also involved various social classes, from the elite to the commoners, in a shared religious experience. The act of sacrifice thus became a focal point for community cohesion.

Moreover, the ritual itself was laden with symbolism. The act of slaughtering an animal represented a gift to the gods, while the subsequent feasting on the sacrificed meat allowed for a communal celebration, bridging the earthly and divine realms. The blood of the sacrificial animal, believed to carry the life force, was often sprinkled on altars or on the ground to sanctify the space and invoke the presence of the gods.

Festivals were integral to the religious calendar of the Archaic Period, serving both as religious observances and public celebrations. Each city-state had its own festivals dedicated to specific deities, reflecting local traditions and agricultural cycles. These events were marked by a variety of activities, including athletic competitions, artistic performances, and feasting.

One of the most famous festivals of the Archaic Period was the Olympic Games, held every four years in Olympia in honor of Zeus. Established in 776 BCE, the Olympics combined athletic prowess with religious devotion, showcasing the best athletes from various Greek city-states. The games were not solely a contest of physical strength but also a demonstration of the unity of the Greek people under the worship of a common deity.

Other significant festivals included the Dionysia, a celebration dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility. This festival featured dramatic performances and was crucial in the development of Greek theater. The rituals associated with the Dionysia often involved processions, where participants would carry phalloi, symbols of fertility, and engage in ecstatic dances that blurred the lines between the sacred and the profane.

Public celebrations during these festivals also highlighted the importance of community participation. They provided an opportunity for citizens to come together, reinforcing social hierarchies while allowing for the expression of civic pride. Festivals often included competitions, where poets, musicians, and athletes showcased their talents, further enhancing the sense of communal identity.

In addition to their religious significance, these festivals served as economic engines for the city-states. As people traveled from various regions to participate in the festivities, local economies thrived through trade and tourism. Thus, festivals in the Archaic Period were multifaceted events that intertwined religion, culture, and economy, demonstrating the complexity of Greek society.

Women played a crucial role in the religious life of the Archaic Period, often serving as priestesses in various cults and rituals. Their participation was vital in maintaining the religious traditions and ensuring the proper conduct of rituals. Women were often responsible for domestic sacrifices and household rituals, thus solidifying their role as the caretakers of the family’s spiritual well-being.

In many instances, women held significant positions within religious institutions. For example, the priestess of Athena in Athens was a respected figure who presided over important rituals, including the Panathenaic Festival. Similarly, cults dedicated to goddesses such as Demeter and Artemis often featured women in prominent roles, highlighting the feminine aspect of spirituality in ancient Greece.

Moreover, female participation in festivals and rituals often included specific rites that celebrated fertility and motherhood. The Thesmophoria, a festival dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, was exclusively for women and focused on fertility and agricultural prosperity. During this festival, women engaged in various rituals aimed at ensuring a fruitful harvest, illustrating how women's roles were deeply intertwined with the agricultural cycles and the well-being of the community.

Despite the restrictions placed on women in many aspects of public life, their involvement in religious rituals provided a space for agency and influence within the community. Through their roles as priestesses and participants in festivals, women contributed to the religious and cultural fabric of the Archaic Period.

The rituals and ceremonies of the Archaic Period were not only expressions of devotion but also reflections of the social structure of ancient Greek society. The organization of rituals often mirrored the hierarchical nature of the community. For instance, prominent families and aristocrats typically had the resources to sponsor large sacrifices and festivals, elevating their status and influence within the city-state.

In many cases, the ability to host public sacrifices or sponsor festivals was a means of demonstrating wealth and power. Elite citizens often sought to gain favor with the gods through lavish offerings, thereby securing their standing within the community. This interplay between religion and social hierarchy was evident during major festivals, where the distribution of roles and responsibilities often favored the elite, while common citizens participated in subordinate capacities.

Moreover, the performance of rituals often reinforced social cohesion and collective identity among the citizens. By participating in communal sacrifices and festivals, individuals were reminded of their shared beliefs and values, fostering a sense of belonging. This collective participation in religious practices helped to stabilize societal norms and expectations, creating a framework within which individuals could navigate their roles in the community.

Furthermore, the rituals associated with death and funerary practices also revealed insights into social hierarchies. The manner in which individuals were buried, the rituals performed, and the offerings made at gravesites often reflected social status. Elite individuals received more elaborate funerals, emphasizing their importance within the community and their relationship with the divine.

In conclusion, the ritual practices and ceremonies of the Archaic Period were complex and multifaceted, deeply embedded in the social, cultural, and religious fabric of ancient Greek life. Through sacrifices, festivals, and the involvement of women, these rituals served to unify communities, reinforce social hierarchies, and express the deeply held beliefs of the people. They were not merely acts of worship but vital components of the societal structure that defined the Archaic Period.

In ancient Greece, the geography of the landscape played a fundamental role in shaping religious practices and beliefs. The diverse topography, consisting of mountains, valleys, and coastlines, influenced where and how communities worshipped their gods. This section will explore the intricacies of local cults, regional variations in worship, and the significance of sacred sites, providing a thorough understanding of how geography intertwined with the religious life of the Archaic Period.

The Archaic Period of Greece, which spanned from approximately the 8th to the 6th centuries BCE, was characterized by a plethora of local cults that arose in response to geographic specificities. Each region developed its own deities, rituals, and places of worship, often reflecting the unique characteristics and needs of the local community.

For instance, in the mountainous regions of Arcadia, the worship of Pan and other nature deities was prevalent. The rugged terrain and isolation fostered a connection to the natural world, leading communities to venerate gods associated with the wilderness. This reverence for nature is evident in the numerous festivals dedicated to these deities, which often included music, dance, and offerings of fruits and animals.

In contrast, coastal cities like Athens and Corinth developed their own distinct religious practices influenced by their maritime environment. The goddess Athena, revered as the protector of the city, held significant importance in Athens, and her temple, the Parthenon, served as a central place of worship. The city’s prosperity through trade and naval power enhanced the prominence of Athena, leading to the establishment of grand festivals such as the Panathenaea, which celebrated her with athletic competitions, processions, and sacrifices.

Moreover, the worship of local gods and heroes was common throughout Greece. Each city-state often had its own patron deity and mythological figures that embodied the identity and values of the community. For example, the hero Heracles was celebrated in various local cults, with each region emphasizing different aspects of his mythology. In Thebes, for instance, he was revered for his strength and heroism, while in other areas, he was associated with agricultural fertility and protection.

Sacred sites played a pivotal role in the religious landscape of ancient Greece, serving as focal points for worship and pilgrimage. Many of these sites were chosen for their geographical features, such as natural springs, mountains, or groves of sacred trees, which were believed to be inhabited by the gods. These locations not only provided a physical space for religious activities but also reinforced the connection between the divine and the natural world.

One of the most significant sacred sites was Delphi, home to the Oracle of Delphi, dedicated to the god Apollo. Situated on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, Delphi was considered the center of the world, and its oracle was revered across Greece for providing prophetic guidance. Pilgrims traveled from distant regions to consult the oracle, underscoring the importance of geography in facilitating religious communication and influence. The site’s geographical setting contributed to its mystique, as the natural landscape was believed to enhance the divine presence of the oracle.

Another vital site was Olympia, where the ancient Olympic Games were held in honor of Zeus. The sanctuary of Olympia housed the massive statue of Zeus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The geographical location, surrounded by lush forests and flowing rivers, created a sacred ambiance that attracted worshippers and athletes alike. The Olympic Games not only celebrated athletic prowess but also served as a unifying event for the Greek city-states, showcasing the importance of geography in fostering cultural and religious connections.

Furthermore, local cults often established sacred groves and altars in natural settings, signifying the integration of religious practices with the environment. These sites were places of worship, offering, and gathering, where communities could express their devotion and seek favor from the gods. The sacredness of these locations was amplified by the belief that they were imbued with divine energy, making them essential to the spiritual life of the community.

The geographical diversity of Greece also led to the establishment of various regional festivals, each reflecting the unique characteristics of the local deities. For example, the Thesmophoria, a festival dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, was celebrated primarily by women and involved agricultural rituals that coincided with the harvest season. The festival's significance was heightened by the agricultural landscape of the region, where the fertility of the land was directly linked to the worship of these goddesses.

The interplay between geography and religion in the Archaic Period also contributed to the development of community identity. Local cults and practices fostered a sense of belonging among the inhabitants of each region. The communal aspect of worship, whether during festivals, sacrifices, or rituals, reinforced social cohesion and solidarity. As different city-states emerged, their unique religious identities often became intertwined with their political and cultural narratives.

Religious practices were not merely individual acts of devotion; they were communal events that brought together people from various social strata. The organization of festivals, the construction of temples, and the performance of rituals required collective effort and participation. This shared experience cultivated a strong sense of identity and belonging, linking individuals to their local community and the pantheon of gods they revered.

In addition, the belief in regional gods and heroes created a strong sense of local pride. Each city-state celebrated its unique myths and legends, reinforcing the idea that their identity was shaped by their geographical surroundings. For example, the citizens of Argos took great pride in their devotion to the hero Perseus, while the people of Mycenae revered Agamemnon. Such local heroes were often commemorated through dedicated temples and festivals, further embedding the connection between geography, community, and religious identity.

The influence of geography on religious practices during the Archaic Period in ancient Greece was profound and multifaceted. Local cults and regional variations reflected the diverse landscapes and cultural identities that characterized the Greek world. Sacred sites served as important geographical markers of divine presence, while rituals and festivals reinforced community bonds and individual identities. The interplay between geography and religion not only shaped the spiritual life of ancient Greeks but also laid the foundation for the development of their cultural heritage, echoing through the centuries to the present day.

The Archaic Period of Ancient Greece, spanning from approximately the eighth to the sixth centuries BCE, was pivotal in shaping the religious landscape that would characterize later Greek culture. Understanding the archaeological evidence of religion and rituals during this time provides significant insights into the spiritual lives of the Greeks. This section will delve into the physical remnants of religious practices, including temples, artifacts, and the interpretation of ritualistic objects, revealing the intricacies of worship and belief in this formative era.

Temples in the Archaic Period were not merely places of worship but also served as repositories of community identity and cultural expression. The earliest temples were simple structures made of mud brick or wood, but as the period progressed, they evolved into more sophisticated stone constructions. The architectural style of these early temples laid the groundwork for the iconic structures of Classical Greece. For instance, the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, although primarily built later, has origins that can be traced back to this earlier period, reflecting the significance of Apollo as a deity of great importance.

Excavations across various sites have uncovered numerous artifacts that provide deeper insights into the religious practices of the time. For example, pottery fragments adorned with depictions of deities, mythological scenes, and ritual practices have been found in places like Olympia and Corinth. These artifacts often illustrate the interactions between gods and mortals, revealing how the Greeks understood their place in the cosmos.

Moreover, many temples housed statues of deities, often made of materials like bronze, marble, and clay. The presence of these idols was central to worship, as they were believed to embody the divine. Statues of gods such as Athena, Zeus, and Dionysus were not only artistic masterpieces but also focal points for ritual activities. The craftsmanship and iconography of these statues provide valuable information about the religious beliefs and aesthetic values of the Archaic Greeks.

Ritualistic objects excavated from various sites offer profound insights into the spiritual practices of the Archaic Period. These objects range from everyday items repurposed for religious use to specialized tools created for specific rituals. For instance, altars have been discovered at many temple sites, often accompanied by remnants of sacrificial offerings. The materials and designs of these altars varied significantly, reflecting local customs and the particular deity honored.

One of the most intriguing categories of ritualistic objects is the votive offerings. These offerings, which included miniature figurines, pottery, and personal items, were left at temples as acts of devotion or in thanks for blessings received. Archaeological finds at sanctuaries such as Delphi and Olympia have revealed a wealth of votive offerings, highlighting the personal connection individuals felt with their deities. The diversity in these offerings indicates not only the different religious practices across regions but also the varying social statuses of the worshippers.

The interpretation of these findings requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining archaeology, art history, and religious studies. Scholars analyze the materials, craftsmanship, and contexts of these artifacts to reconstruct the rituals they were part of and the meanings they held for the ancient practitioners. For example, the study of animal bones found at altar sites provides insights into the types of sacrifices performed and their significance within the broader context of religious observance.

Furthermore, the presence of tools associated with specific rituals, such as the knives used for sacrifices or incense burners, reveals the meticulous nature of Archaic religious practices. These objects were not merely functional; they were imbued with meaning and were often crafted with care, indicating the reverence with which the Greeks approached their rituals. Each tool held a specific role within the ritualistic framework, emphasizing the importance of order and tradition in religious observance.

Understanding the temporal aspects of rituals is crucial to grasping their significance in Archaic Greece. Rituals were often bound to the cyclical nature of the agricultural calendar, with many festivals coinciding with planting and harvest times. This relationship between time and ritual is evident in the archaeological record, where evidence of seasonal festivals is often accompanied by specific offerings or artifacts related to agricultural deities.

The calendar of religious festivals was meticulously observed, and evidence from inscriptions suggests that certain rituals were repeated annually, creating a rhythm of worship that reinforced community identity. Sites such as Eleusis, known for its mystery cults, highlight the importance of timing in religious practices, where specific rites were performed only during certain times of the year, deepening the connection between the divine and the cyclical nature of life.

Art from the Archaic Period plays a significant role in understanding the religious landscape of the time. Pottery, sculpture, and frescoes provide visual narratives that depict religious beliefs and rituals. The famous black-figure and red-figure pottery styles, for instance, often featured scenes of gods, heroes, and mythological events, serving both decorative and educational purposes. These artistic representations allowed the Greeks to convey complex religious narratives and reinforce communal beliefs.

Moreover, the artistry of these pieces reflects the cultural values of the Archaic Greeks. The careful representation of deities in various forms—whether as anthropomorphic figures or symbolic representations—illustrates the evolving understanding of divinity. Such artworks not only served a religious purpose but also acted as a bridge between the sacred and the everyday, allowing individuals to connect with their beliefs in a tangible way.

The archaeological evidence also highlights the regional variations in religious practices across Ancient Greece. Different areas displayed unique characteristics in their worship, influenced by local customs, environmental factors, and interactions with neighboring cultures. For example, the cult of Dionysus was particularly prominent in regions like Boeotia and Attica, where specific types of pottery and artifacts associated with the god of wine and festivity have been unearthed. The differences in worship practices underscore the diversity of beliefs and the adaptability of Greek religion to local contexts.

Additionally, regional sanctuaries often developed distinct characteristics based on local deities venerated and the rituals performed. The establishment of sanctuaries such as Delphi, dedicated to Apollo, and Olympia, associated with Zeus, illustrates how geography influenced the cults that flourished there. The resulting archaeological evidence, including inscriptions, artifacts, and architectural remains, provides a rich tapestry of the religious life of different regions, showcasing the interplay between environment, culture, and spirituality.

Religion in the Archaic Period was deeply intertwined with community identity. The archaeological evidence suggests that religious practices were often communal affairs, reinforcing social bonds and collective identity among the people. Festivals and rituals brought communities together, allowing them to express their devotion collectively while celebrating their shared cultural heritage.

Excavations at sites like Corinth and Athens have revealed large public spaces designed for communal worship and celebration, reflecting the importance of these gatherings. The architecture of these sites often included altars, seating areas, and processional paths, all of which facilitated communal participation in religious events. The organization of such events required cooperation and collaboration, further strengthening community ties.

Moreover, the participation in rituals served as a means of establishing social hierarchies and roles within the community. Different groups, such as families, clans, and city-states, often had specific responsibilities during rituals, highlighting the interplay between religion and social structure. This communal aspect of religion not only fostered a sense of belonging but also shaped individual identities within the larger societal framework.

In conclusion, the archaeological evidence of religion and rituals in the Archaic Period of Ancient Greece reveals a complex and dynamic spiritual landscape. Temples, artifacts, and ritualistic objects provide invaluable insights into the beliefs, practices, and community life of the Greeks during this formative era. By examining these remnants, we gain a deeper understanding of how religion was intricately woven into the fabric of daily life, shaping not only individual identities but also the collective identity of communities across the Greek world.